by Sara Robinson

Per Digby:

[Amy] Sullivan believes that in order to appeal to evangelicals we must not only study their theology in detail so as to understand why they follow some lunatic like Pat Robertson but we are supposed to be tolerant of what would be called racist or religiously intolerant statements from anyone else because they believe it derives from the Bible. Oy.

Oy indeed. As we've discussed here at some length: studying fundamentalist theology is almost entirely beside the point. On the other hand, studying their psychology and sociology -- which a great many people have already done -- and using that information to understand what they value and how they communicate will get us much, much farther.

Digby's characterization of Sullivan's beliefs sounds like another earnest example of the liberal conviction that "if we just reason with them and give them the facts, they'll be persuaded and come around." Huh-uh. Not these folks. They're not reality-based, remember? You can talk facts at them all day, and get nowhere. The Democrats done it for decades, and we can all see how well that's turned out for them. These True Believers eat contradictions for breakfast, and lies from their leadership for lunch. Facts mean nothing, no matter how sound they are; and trying to "understand how they think" will only make you as crazy as they are.

The key is to get them to feel your message. The recent evangelical embrace of the global warming message may have come about because Al Gore, being a product of Southern Baptist culture himself, knew how to present the issue in a way that liberals could understand intellectually -- but, at the same time, religious conservatives could feel emotionally. My friends and I were sitting there in the theater, watching those scenes down on the farm in Carthage, TN, and wondering what in the hell this had to do with anything. As hard-headed science-based types, our major take-away from An Inconvenient Truth were the charts -- especially the one with the red line showing C02 levels going straight up off the right-hand edge. But I suspect that if you asked an evanglical what he or she remembers, you'd hear about those scenes from Carthage, and the way those intimate little family stories spoke to their hearts. Gore is a very smart man, and he knows his audience well.

We register information. They register emotion. It's a critical difference, and one that should be kept in mind whenever we try to communicate with the religious right. We want PBS documentaries that give us a deeper understanding of the facts; they want melodrama that grabs 'em by the guts and makes them feel the truth (which is why Foley gets through to them in a way that Iraq does not.) Understand this, and the theology is moot.

As for tolerance: Oh, please. One of the gravest errors liberals have made over the past 40 years is our ongoing failure to ask our conservative friends the hard questions about their beliefs. We wanted to be inclusive. We wanted to respect their religious views. We didn't want to make them squirm. We were being oh so tolerant.

Well, damn it -- sometimes, people who are in error should be made to squirm a little. They should be called to account for their views, and queried thoroughly on what their agenda is for the rest of us. There comes a time when politeness has to take a back seat to the larger interests of the country -- and we passed that moment way back in the early Reagan years.

Americans on all sides are amazingly ignorant of what "tolerance" means in a country that relies on the free marketplace of ideas to sustain democracy. This is the kind of stuff that used to be taught in civics classes back in the day. For those who aren't clear on the concept, here's a review.

Free speech, in the American tradition, has always meant that you cannot be persecuted by the government for speaking your mind. The government cannot harass you or jail you for your associations, your political views, or your religious beliefs. (Or, at least, they couldn't, right up until last Monday.) It does NOT mean that the rest of us non-government types are required to hold our tongues and smile while people say things that are stupid, dangerous, or contrary to fact. In fact, it means we are duty-bound as citizens to stand up and say, as loudly as necessary, "No. That's a bad idea. And here's why."

The free marketplace of ideas is based on the premise that good ideas drive out bad ones; and that the more voices that we hear, the more choices we'll have and the better decisions we'll make. It is grounded in the belief that some ideas are better than others; and only by free and open exchange will the very best ones emerge. If that exchange stops because our vaunted liberal tolerance renders us too polite and forgiving to raise our voices against patently stupid ideas, the marketplace ceases to function, stupidity wins, and democracy decays. Simple enough, right?

It is not just wrong, but downright unpatriotic, for us to let the right wing get away with making racist or intolerant statements just because they assert that their Bible backs up such views. For one thing: there's plenty in the Bible that refutes racism and intolerance. For another: harmful ideas are no less harmful just because they're written in King James English and dressed up in Sunday clothes. For a third: it's time to stop using tolerance as an excuse for politically cowardly behavior. The stakes these days are just too high to let the right wing go about its nasty business, unchallenged and unanswered.

Update:

Various commenters seemed to interpret this as an argument that liberals don't feel emotion, or religious conservatives don't think -- which is extending my point a little farther than it's intended to go. One asked about how this fits into George Lakoff's thesis about the different family frames used by conservatives and liberals. I'd like to address both, since they're related.

The topic here is communication styles, about how you get people to pay attention and understand a message. Liberals and conservatives have very different attitudes toward information, and prioritize it differently as it comes in. One way to understand this is through Lakoff's parenting frames.

In the nuturing-parent paradigm, families are run on a fairly (not entirely) flat hierarchy, and the parent's function is to prepare the child to function on its own. In this model, everybody is encouraged to make their own decisions to the extent that they're competent to do so -- and to continue to grow in that competence.

To do that, you need information, and practice in thinking for yourself -- both of which are important gifts that the parent provides. The end result is a child who has a firmly internalized locus of control, who is competent to direct his or her own life according to his or her own lights. This is why liberals crave real-world facts and information. The more we have, the better we function in the world, and the greater our agency in our own lives.

In the strict father paradigm, families are hierarchical, since the father's main duty is to provide for and protect his offspring. In this model, the locus of control is externalized -- Dad runs everything, and the child's duty is to obey his rules without question. It's for your own good.

This model encourages Dad to maintain a greater monopoly on information. Rules and commands come down from Dad On High, who may or may not clue you in to why he's doing what he's doing. You don't need that information, because the parent's function is to make all the decisions (he's the Decider), and the child's role is to follow them without question. Too much information just leads to second-guessing, which gets in the way of the obedience that's needed to make the system work.

Followers in SF systems take comfort in not having to make their own decisions. They're happy to have Dad handle the complicated parts of the world, and value the security they feel as a result of being under Dad's care. Altemeyer's work on right-wing followers discussed this childlike emotional stance at some length. You might also take another look at Tuesday's "Another Country Heard From" post below, which discusses the emotional appeal of authoritarian religion.

Both sides use both emotion and feeling -- but they use it toward very different ends. NPs love their kids by empowering them to function as autonomous adults -- an attitude that privileges learning over sentimentality. For us, the facts lead, and we try to manage our emotions so that they fit the factual reality. SFs love their kids by providing for them and protecting them from the world -- an attitude that privileges sentimentality over learning. For them, the heart leads, and the facts only follow if they fit what their emotions tell them.

And that's how you get to this split in communication styles.

Saturday, October 21, 2006

Thursday, October 19, 2006

There's Something About The Men

by Sara Robinson

Excerpted from Wikipedia:

Militia members, gun nuts, hate criminals, fundamentalists, Minutemen, high-social dominance authoritarian leaders, submissive authoritarian followers, guys like the one below, guys like the ones above. Over the years, we've had a lot of conversations here trying to figuring out what makes them tick, where they want to take us, how we can keep from going there -- and perhaps most plangently: why do we seem to have so many of them? Often, if we talk about it long enough, the conversation always seems to come back to one place. And there it stops, as if on the edge of something vast and terrifying that we simply cannot bring ourselves to grapple with.

Something is not right with the boys. Something in the way Americans look at males and manhood has gone sour, curdling into to a rank, toxic, and nasty brew that is changing the entire flavor of our culture. Men everywhere seem to be furious. Some turn it outward against women, against society, against the institutions that no longer seem to nurture them. Some turn it inward against themselves, putting their energies into bizarre self-destructive fantasy lives centered around money, violence, and sex. Some, more disenchanted than angry, check out entirely, abdicating any interest in making commitments or contributions to a family, a profession, or a community to spend their lives as perpetual Lost Boys. Together, all this misdirected, destructive energy has become a social, cultural, and political liability that we can no longer afford to ignore.

As the old preacher asked in the opening scenes of The Big Chill: "Are the satisfactions of being a good man among our common men no longer enough?" Given the number of men who seem to be completely disconnected from the very idea of the greater good, let alone the thought that they have any responsibility to it, the answer seems to be: No. They're not.

The facile answer, of course, is to blame feminism. Many of these angry men will eagerly tell you that that’s exactly right, brother. If our mothers and grandmothers had simply kept in their places and not stepped forward in the 60s and 70s, none of this would have happened. And they'd have been just fine. It's those damned pushy women, taking away our jobs and our private spaces and our guns….

This is a fruitless argument: in retrospect, there were dozens of inarguable reasons that feminism had to happen. And in most of the ways that matter, we're a better, stronger society because it did. Forty years later, we women are well along in the process of re-defining our social roles. It's still rough in spots, but we're starting to see the outline of what our new, more equal world is going to look like when it's done. We’re not OK yet, but we can believe that we are going to be.

But maybe what we are seeing here is a loose end, a leftover bit of unfinished business that hasn't even begun to be addressed yet. Maybe, for the men, the process of re-creating their place in our culture has hardly even started -- and their confidence in the enterprise is far less certain. While the shift has generally worked out well for men who had the education and resources to process and adapt to it, there are apparently a great many men who are still deeply grieving the loss of our widely-shared traditional assumptions about what makes a man, and what men are supposed to contribute to the larger society.

Without those assumptions to give their lives structure and meaning, these guys are drifting -- not sure how they fit in, or what they're supposed to contribute, or what separates the men from the boys in this rearranged new world. And some of them, as we've seen here, are drifting off in very dangerous directions as they try to express a little manhood in a world where it doesn't seem to mean much any more.

The right wing has very aggressively stepped forward with all kinds of answers to salve their souls. The military. NASCAR. Promise Keepers. The Boy Scouts. And, more ominously, the KKK and the militias and the Minutemen. The conservative Cult of Maleness is full of tradition and ritual, conformity and hierarchy, the stuff of which male cultures have always been made. (Social psychologists now think the last two are actually a direct function of testosterone. In other words, men can't help acting that way: it's hormonal.) Say what you will about all this puffed-up patriarchal posturing, but the fact remains: these made-for-men bonding ops seem to be channeling some powerful energy, and fulfilling some yawning emotional needs.

The left, on the other hand, hasn't given them much at all. And we probably won't be able to until we finally come around to admitting that men and women are different -- perhaps not to the acute degree that the traditional sterotypes once enforced so strictly, but also not as superficially as the forced androgyny of liberal culture has tried to pretend. We come equipped with different physiology and different hormone sets; and we still get different messages from the culture about gender expectations. Denying that has led to some widespread assumptions and social choices that have been unfair to both men and women. It has also brought us to this impasse where so many men are disengaging from the common good altogether, because they don't believe there's any upside in it for them.

Perhaps, after four decades, a little realism is called for. It may be time for the progressive community to have an honest discussion about why these guys are angry; what they feel like they've lost; and how we're going to rebuild a new definition of manhood that meets their deepest emotional, social, and spiritual needs without also bringing on the resurrection of the late-but-not-lamented macho asshole. It may be time for women to figure out how we can encourage men to complement us -- not by suppressing the things that make them different from us, but by expressing those different (and, to most of us, delightful) qualities in ways that we can genuinely celebrate and value -- and that will benefit us all.

We have been here before. Detached, disaffected, angry boys with guns were a national scourge during and after the Civil War. Gangsters made city neighborhoods violent in the years just before and during the Depression. I'd like to think we're going to get through it this time, too.

But we will not stop it -- nor prevent its reoccurrence in the years ahead -- until we come to grips with the deeper reasons so many men are angry, and start figuring out how we are going to address that rage at its root. It's time for that discussion to begin.

Excerpted from Wikipedia:

September 13, 2006, Montreal, Quebec, Canada; A 25-year-old man started firing at the entrance to Dawson College, and proceeded on a rampage to the college's cafeteria. One victim died at the scene. Another 19 were injured. The gunman later committed suicide by shooting himself in the head, after being shot in the arm by police.

September 14, 2006 Ottawa, Ontario, Canada; A 22-year-old university law student fired a pellet gun at one of the buildings of the University of Ottawa in a drive-by shooting. He was quickly arrested at his home and was subsequently banned from the University. No one was injured.

September 15, 2006 Green Bay, Wisconsin, USA; Two 17-year-old boys and one 18-year-old boy were arrested on suspicion of a possible shooting attack at Green Bay East High School. News reports said they were depressed and were fascinated with Columbine. Numerous weapons were found in their homes.

September 16, 2006 St. Louis, Missouri, USA; A senior student of Westminster High School, Austin Vincent, reportedly text-messaged his friend, saying he would commit suicide. This was later forwarded to a counselor, who called the police. He did not attend school on September 16. School got out at 3:00, and he arrived around 3:45. He got out of his mother's car holding a rifle. Police were already on the scene. Vincent reportedly pointed the rifle at his head, then waved it at the police. Officers took 3 shots, and he was hit in the leg by at least one. He was taken to a hospital in stable condition. He would later be tried as an adult.

September 18, 2006 Hudson, Quebec, Canada; A 15-year-old was arrested after uttering death threats via the same Internet site as Dawson College shooter Kimveer Gill. He was planning a similar type shooting at a high school west of Montreal.

September 27, 2006 Bailey, Colorado, USA; Duane Roger Morrison, a 53-year-old man, entered Platte Canyon High School, reportedly saying that he had a bomb. Morrison took six female students as hostages, later releasing four of them whilst keeping two. One of the remaining hostages was shot, wounded critically and taken away by air ambulance. The other was not wounded. Paramedics at the scene confirmed that Morrison shot and killed himself.

September 29, 2006 Cazenovia, Wisconsin, USA; At Weston High School, 15-year-old Eric Hainstock shoots his high school principal, who then managed to wrestle Hainstock to the ground. The principal died later in hospital from multiple gunshot wounds.

October 2, 2006, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, USA; A gunman took hostages and eventually killed five girls (aged 7–13) and himself at West Nickel Mines School, a one-room Amish schoolhouse.

October 2, 2006 Cincinnati, Ohio, USA; A 15-year-old freshman was arrested at his home when he sent a text message threatening to bring his gun to a local high school. The school was locked down while police arrested the suspect, but re-opened in time for classes.

October 2, 2006 Las Vegas, Nevada, USA; An ex-student of Mohave High School went on campus with a gun, his motive unknown at the time. Students recognized him as not being a student anymore and notified school police immediately. The suspect ran from the school and ditched his gun behind a church close to Mohave. Mohave, as well as 3 middle schools and 1 elementary school were placed on lockdown while police searched for him.

Militia members, gun nuts, hate criminals, fundamentalists, Minutemen, high-social dominance authoritarian leaders, submissive authoritarian followers, guys like the one below, guys like the ones above. Over the years, we've had a lot of conversations here trying to figuring out what makes them tick, where they want to take us, how we can keep from going there -- and perhaps most plangently: why do we seem to have so many of them? Often, if we talk about it long enough, the conversation always seems to come back to one place. And there it stops, as if on the edge of something vast and terrifying that we simply cannot bring ourselves to grapple with.

Something is not right with the boys. Something in the way Americans look at males and manhood has gone sour, curdling into to a rank, toxic, and nasty brew that is changing the entire flavor of our culture. Men everywhere seem to be furious. Some turn it outward against women, against society, against the institutions that no longer seem to nurture them. Some turn it inward against themselves, putting their energies into bizarre self-destructive fantasy lives centered around money, violence, and sex. Some, more disenchanted than angry, check out entirely, abdicating any interest in making commitments or contributions to a family, a profession, or a community to spend their lives as perpetual Lost Boys. Together, all this misdirected, destructive energy has become a social, cultural, and political liability that we can no longer afford to ignore.

As the old preacher asked in the opening scenes of The Big Chill: "Are the satisfactions of being a good man among our common men no longer enough?" Given the number of men who seem to be completely disconnected from the very idea of the greater good, let alone the thought that they have any responsibility to it, the answer seems to be: No. They're not.

The facile answer, of course, is to blame feminism. Many of these angry men will eagerly tell you that that’s exactly right, brother. If our mothers and grandmothers had simply kept in their places and not stepped forward in the 60s and 70s, none of this would have happened. And they'd have been just fine. It's those damned pushy women, taking away our jobs and our private spaces and our guns….

This is a fruitless argument: in retrospect, there were dozens of inarguable reasons that feminism had to happen. And in most of the ways that matter, we're a better, stronger society because it did. Forty years later, we women are well along in the process of re-defining our social roles. It's still rough in spots, but we're starting to see the outline of what our new, more equal world is going to look like when it's done. We’re not OK yet, but we can believe that we are going to be.

But maybe what we are seeing here is a loose end, a leftover bit of unfinished business that hasn't even begun to be addressed yet. Maybe, for the men, the process of re-creating their place in our culture has hardly even started -- and their confidence in the enterprise is far less certain. While the shift has generally worked out well for men who had the education and resources to process and adapt to it, there are apparently a great many men who are still deeply grieving the loss of our widely-shared traditional assumptions about what makes a man, and what men are supposed to contribute to the larger society.

Without those assumptions to give their lives structure and meaning, these guys are drifting -- not sure how they fit in, or what they're supposed to contribute, or what separates the men from the boys in this rearranged new world. And some of them, as we've seen here, are drifting off in very dangerous directions as they try to express a little manhood in a world where it doesn't seem to mean much any more.

The right wing has very aggressively stepped forward with all kinds of answers to salve their souls. The military. NASCAR. Promise Keepers. The Boy Scouts. And, more ominously, the KKK and the militias and the Minutemen. The conservative Cult of Maleness is full of tradition and ritual, conformity and hierarchy, the stuff of which male cultures have always been made. (Social psychologists now think the last two are actually a direct function of testosterone. In other words, men can't help acting that way: it's hormonal.) Say what you will about all this puffed-up patriarchal posturing, but the fact remains: these made-for-men bonding ops seem to be channeling some powerful energy, and fulfilling some yawning emotional needs.

The left, on the other hand, hasn't given them much at all. And we probably won't be able to until we finally come around to admitting that men and women are different -- perhaps not to the acute degree that the traditional sterotypes once enforced so strictly, but also not as superficially as the forced androgyny of liberal culture has tried to pretend. We come equipped with different physiology and different hormone sets; and we still get different messages from the culture about gender expectations. Denying that has led to some widespread assumptions and social choices that have been unfair to both men and women. It has also brought us to this impasse where so many men are disengaging from the common good altogether, because they don't believe there's any upside in it for them.

Perhaps, after four decades, a little realism is called for. It may be time for the progressive community to have an honest discussion about why these guys are angry; what they feel like they've lost; and how we're going to rebuild a new definition of manhood that meets their deepest emotional, social, and spiritual needs without also bringing on the resurrection of the late-but-not-lamented macho asshole. It may be time for women to figure out how we can encourage men to complement us -- not by suppressing the things that make them different from us, but by expressing those different (and, to most of us, delightful) qualities in ways that we can genuinely celebrate and value -- and that will benefit us all.

We have been here before. Detached, disaffected, angry boys with guns were a national scourge during and after the Civil War. Gangsters made city neighborhoods violent in the years just before and during the Depression. I'd like to think we're going to get through it this time, too.

But we will not stop it -- nor prevent its reoccurrence in the years ahead -- until we come to grips with the deeper reasons so many men are angry, and start figuring out how we are going to address that rage at its root. It's time for that discussion to begin.

Wednesday, October 18, 2006

The other kind of terrorist

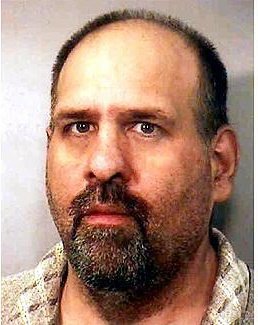

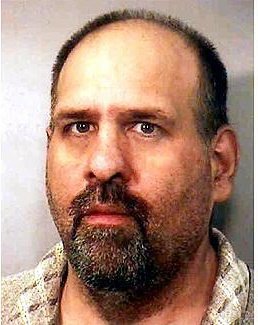

Hey, here's another addition to that gallery (inspired by Michelle Malkin) of terrorists who happen to be white fundamentalist fanatics:

This charming fellow is David McMenemy, who decided to try to set the Edgerton Women's Health Clinic in Davenport, Iowa, on fire -- by dousing his car with gasoline and driving into it an apparent suicide-bombing attempt:

McMenemy's family later professed amazement at this turn of events, but McMenemy in fact had a long history of mental instability.

That's a theme running through a lot of these kinds of acts of terrorism, as I've noted before:

Jennifer Pozner's Newsday column hits the target precisely:

One can only imagine Malkin's reaction as well.

Of course, in this case, the intended targets were the abortion providers in McMenemy's fevered imagination, but even more generically, it was women generally:

When the fanatics of the religious right talk about being solely concerned about the life of the fetus, it's perhaps useful to take into account the broad effects of their fanaticism. Because then the reality of what they are about comes into focus.

Being against abortion isn't about the sanctity of life. It's about controlling women. And the terrorists at whom they wink and nudge are part of how they keep them in line.

This charming fellow is David McMenemy, who decided to try to set the Edgerton Women's Health Clinic in Davenport, Iowa, on fire -- by dousing his car with gasoline and driving into it an apparent suicide-bombing attempt:

- A Michigan man described as a bookworm by relatives has wandered the Midwest since August, looking for a medical clinic to attack with his 2004 Saturn compact car, authorities said.

It was dawn Monday when David Robert McMenemy approached Edgerton Women's Health Center in Davenport, which he mistakenly believed provided abortions.

He entered the center's driveway off East Rusholme Street and then took a few moments to turn and configure the car to face straight into the lobby, Davenport Fire Marshal Mike Hayman said.

The 45-year-old crashed the Saturn into the central lobby, coming to rest at the counter. When the car did not immediately burst into flames as he may have expected, police said he took gasoline that he had poured into a Gatorade bottle and spread it over the interior. "I lit it," McMenemy told investigators, and he exited the structure to surrender himself to startled Davenport firefighters.

"He came out and said to our guys, 'There's no one in the vehicle, and that's my car. I did it,'" Hayman related. "Our commander on the scene was very surprised, and he took McMenemy to a squad car and turned him over to police."

The health center would have been destroyed if its sprinkler system hadn't activated, police reported. Damage estimates were not available late Tuesday.

McMenemy's family later professed amazement at this turn of events, but McMenemy in fact had a long history of mental instability.

That's a theme running through a lot of these kinds of acts of terrorism, as I've noted before:

- Marking off rampages like Furrow's, Huff's, and Haq's as "isolated events" caused by mental illness is a cop-out, however. Because, as the case of David Lewis Rice made all too clear, these mentally unstable types are almost always stirred up and driven to their insane acts by haters of various stripes, the kind whose voices seem each day to be growing louder in our public discourse. These cultural vampires have developed a real knack for inspiring mentally unstable people into horrific acts of violence.

Jennifer Pozner's Newsday column hits the target precisely:

- On Sept. 11, 2006, the fifth anniversary of the terror attacks that devastated our nation, a man crashed his car into a building in Davenport, Iowa, hoping to blow it up and kill himself in the fire.

No national newspaper, magazine or network newscast reported this attempted suicide bombing, though an AP wire story was available. Cable news (save for MSNBC's Keith Olbermann) was silent about this latest act of terrorism in America.

Had the criminal, David McMenemy, been Arab or Muslim, this would have been headline news for weeks. But since his target was the Edgerton Women's Health Center, rather than, say, a bank or a police station, media have not called this terrorism -- even after three decades of extreme violence by anti-abortion fanatics, mostly fundamentalist Christians who believe they're fighting a holy war.

One can only imagine Malkin's reaction as well.

Of course, in this case, the intended targets were the abortion providers in McMenemy's fevered imagination, but even more generically, it was women generally:

- Which brings us back to car bomber McMenemy. According to the Detroit Free Press (the only newspaper in the Nexis news database that reported his crime), he targeted the women's health center because he thought it provided abortions. It doesn't. (Oops!) It provides mostly low-income patients with pap smears, ob-gyn care, testing for sexually transmitted diseases, birth control, and nutrition and immunization programs for women and children.

The attack caused $170,000 in property damage and left poor families without health care for a week. But long after Edgerton's water-logged carpets are removed, scorched medical equipment replaced and new doors reopened to the public, a culture of fear will linger among doctors, nurses, advocates and patients across the country, who will worry that they're next. Some frightened workers will quit their jobs; some women will be too scared to get the health care they need.

When the fanatics of the religious right talk about being solely concerned about the life of the fetus, it's perhaps useful to take into account the broad effects of their fanaticism. Because then the reality of what they are about comes into focus.

Being against abortion isn't about the sanctity of life. It's about controlling women. And the terrorists at whom they wink and nudge are part of how they keep them in line.

Tuesday, October 17, 2006

Grim news for killer whales

Normally, the end of summer is a time when whale researchers can breathe a little easy when it comes to the Puget Sound's endangered orcas. For the most part, they get their fill of what is usually plenty of fish over the course of the summer. Typically, it's been during the winter months -- when they generally feed off the contintental shelf -- that we seem to have been losing them.

But the Center for Whales Research's annual fall surveys bring some grim news -- three adult orcas are missing -- two of them breeding females:

- Three young adult killer whales - members of the family groups that spend their summers chasing salmon around Washington's San Juan Islands - have not been seen in weeks and are feared dead, researchers said Tuesday.

One of the orcas leaves a 4-month-old orphan, whose care apparently has been taken over by another female.

The three salmon-eating orca families that frequent the state's inland waters are J, K and L pods. J-pod spends virtually the entire year in the waters north of Puget Sound, while the other two groups head out to the open ocean in winter.

The pods, called the southern resident population, are unique in diet, language and DNA, and were declared an endangered species last year, with a recovery goal of 120 animals. If the three missing whales have died, the three pods will total 87 orcas, with just 23 reproductive females.

The missing mother, K-28, is from K-pod, said Kelley Balcomb-Bartok, a research assistant at the Center for Whale Research in Friday Harbor, which tracks the pods and maintains photo-identification records of each animal.

A photo of K-28 taken Sept. 1 shows a dip behind her blowhole, which indicates illness or malnutrition, he said. The 12-year-old female may also have had difficulties related to the birth.

A news release from the Center for Whale Research (via Orca Network) has more details:

- The most troubling information that particularly concerns staff at the Center for Whale Research is the possible loss of K28, a 12 year-old mother, who leaves behind a four month-old orphaned calf. Killer whale calves generally do not begin to eat solid foods until they are at least a year old - and are not fully weaned of mother's milk until nearly two years of age - making it questionable whether K28's calf, K39, will survive the winter.

... If L43 is dead, she leaves behind a two year-old son, L104, a 10 year-old son, L95, and a 20 year-old daughter, L72, with two year-old grand-daughter, L105.

If L71 is dead, he leaves behind his mother, L26, his 13 year-old sister L90, and an 11 year-old nephew, L92. L71's death will be the most recent in a series of losses for matriarch L26. In 2002, L26's first born daughter, L60, washed up at Long Beach, along the coast of Washington state, orphaning her grand-daughter L92. L26's second calf died at the age of three in 1983. In 1997, her grandson, L81, died at the age of

seven.

Though the Southern Resident Orca population may have temporarily reached 90 individuals in 2006 with the addition of the three new calves, the three recent missing whales will return the population to 87. We hope that at least one more calf will be born in this population before year end.

This isn't a good sign. Losing adults, especially of breeding age, damages the population's ability to sustain itself long-term. Replacing them with calves is a start, but it doesn't resolve the immediate issues.

The party of values

The image of the Republican Party as a ruling entity that has been emerging in recent weeks -- helped in large part by the Foley scandal -- is not a pretty one.

It's rather like the fellow who announces his patriotic and moral virtue by wrapping himself in an American flag -- and then uses it to flash the kids at the local schoolyard. ("Hey boys, want to see my torture policy?")

The image was only consolidated further over the weekend by the revelations in the Los Angeles Times about Ken Mehlman's long associations with the corrupt Republican lobbying cabal headed by Jack Abramoff. Those associations, of course, are rather at variance with Mehlman's earlier claims.

But the Times story was almost as noteworthy for what revealed about the peculiar Republican brand of morality:

- For five years, Allen Stayman wondered who ordered his removal from a State Department job negotiating agreements with tiny Pacific island nations — even when his own bosses wanted him to stay.

Now he knows.

Newly disclosed e-mails suggest that the ax fell after intervention by one of the highest officials at the White House: Ken Mehlman, on behalf of one of the most influential lobbyists in town, Jack Abramoff.

The e-mails show that Abramoff, whose client list included the Northern Mariana Islands, had long opposed Stayman's work advocating labor changes in that U.S. commonwealth, and considered what his lobbying team called the "Stayman project" a high priority.

"Mehlman said he would get him fired," an Abramoff associate wrote after meeting with Mehlman, who was then White House political director.

It's worth remembering just what kind of conditions that Stayman was working to change. A 1999 report in Salon on Tom DeLay's connections to the Saipan sweatshops gave us a small portrait, including a discussion of how the sweatshops came to be in the first place:

- It was around this time, however, that mandarins from Hong Kong and the People's Republic of China began setting up textile factories on Saipan and importing labor from the mainland, as well as from Bangladesh and the Philippines, to cut and stitch cloth for garment makers including JC Penney, the Gap, Tommy Hilfiger, Liz Clairborne, Jones New York, Abercrombie & Fitch, Levi Strauss, Nautica and many others -- a virtual Who's Who of designer labels. The idea was to slip under the radar of U.S. quotas and duties, which would cost the manufacturers millions more if the garments were made outside U.S. territory. Garments from Saipan are made from foreign cloth, assembled by foreign workers on U.S. soil and labeled "Made in the USA."

And they are made cheaply. Wages in the factories average about $3 per hour -- more than $2 less than the U.S. minimum wage of $5.15. No overtime is paid for a 70-hour work week. But that's hardly the worst of it. Far away from the swank beachside hotels, luxurious golf courses and the thousands of Japanese tourists snorkling around sunken U.S. Navy landing craft in the clear waters, some 31,000 textile workers live penned up like cattle by armed soldiers and barbed wire, and squeezed head to toe into filthy sleeping barracks, all of which was documented on film by U.S. investigators last year.

The unhappy workers cannot just walk away, either: Like Appalachian coal miners a generation ago, they owe their souls to the company store, starting with factory recruiters, who charge Chinese peasants as much as $4,000 to get them out of China and into a "good job" in "America." Their low salaries make it nearly impossible to buy back their freedom. And so they stay. The small print in their contracts forbids sex, drinking -- and dissent.

"I am very tired," wrote Li Zhen Hua, a 29-year-old Chinese woman in a letter to a friend obtained by the weekly Dallas Observer. "I want to go back to my country but I can't because we must keep [sic] two years ... Very busy. So hard. Every day work up to 1:30. I've to work on Sunday. Too much to respond to your letters."

Another report from a Saipan newspaper goes into more detail:

- The one worker I have access to for this article hasn't been paid in eight weeks. He usually works seven days a week, but receives no overtime pay for such toil. He would like to be able to get a glimpse of Saipan's beaches and sunshine, but he says that he's so overburdened with his job that he seldom has a chance to venture outside.

The worker has no retirement benefits. No health benefits, either. And dental insurance? Get real.

He has no paid vacation. No paid holidays. And if he's sick and can't work, then he loses pay, so he is essentially forced to work even if he has the flu of a fever.

His skin has the pallor of someone who has spent too long under artificial lighting, and not enough time under the sun's rays.

The work space is a chaotic nightmare of clutter. A broken chair--a clear violation of OSHA standards--sits in a musty corner.

The lighting is dim because the lightbulb broke yesterday. It hasn't been replaced because the company is so stingy it has forbidden any corporate expenditures until the end of the month.

The worker gets headaches, occasionally, from being overworked. And perched on an old file cabinet is a dusty jar of Rolaids. Contents: five and a half Rolaids, and two dead ants.

This worker came to Saipan from a vast and distant land, lured by promises of a better life. The promises wilted in the harsh reality of corruption and nepotism and shady government dealings.

While the softbellies were at home, heaping the turkey onto their Thanksgiving plates, the sweatshop worker put in a full day at work, and then a full evening, pausing only for a bit of chicken for dinner. His pay for the day: nothing.

And he worked, too, on Christmas. No pay for that, either.

He doesn't complain, however. He figures it's his station in life to work where he works. Some of his friends here are in the same position, finding themselves working harder and harder for less and less compensation. They occasionally find an hour or two to pop a cold beer, and they sit outside and discuss their situations in Saipan.

Of course, Stayman was hardly the only person trying to change conditions in Saipan. Another, as Mark Shields pointed out last year, was Frank Murkowski, that arch-conservative Republican from Alaska. He too was railroaded by DeLay:

- Moved by the sworn testimony of U.S. officials and human-rights advocates that the 91 percent of the workforce who were immigrants -- from China, the Philippines, Sri Lanka and Bangladesh -- were being paid barely half the U.S. minimum hourly wage and were forced to live behind barbed wire in squalid shacks minus plumbing, work 12 hours a day, often seven days a week, without any of the legal protections U.S. workers are guaranteed, Murkowski wrote a bill to extend the protection of U.S. labor and minimum-wage laws to the workers in the U.S. territory of the Northern Marianas.

So compelling was the case for change the Alaska Republican marshaled that in early 2000, the U.S. Senate unanimously passed the Murkowski worker reform bill.

But one man primarily stopped the U.S. House from even considering that worker-reform bill: then-House Republican Whip Tom DeLay.

Of course, there's no small irony that just this week, George W. Bush declared this "National Character Counts Week."

Indeed it does. Which may have something to do with those polls showing the nation's increasing abhorrence for the Republican version of "values."

Another Country Heard From

by Sara Robinson

Sometimes our random wanders around the Web can turn up some pretty exotic gems. This one ranks among the sparklier baubles I've found stuck in the strands this year.

It's a 2005 article by Dr. Salman Akhtar, a professor of psychiatry at the University of Delhi who's also (quite clearly) a capable and insightful philosopher. In the article, he lays out his understandings of why people turn to fundamentalism -- though his conclusions are probably extensible to most other forms of authoritarianism as well.

"Sanity," says Akhtar, "has its own burdens, and fundamentalism is the treatment for those burdens." His argument spins on six specific burdens of sanity:

-- Factual uncertainty: the need to carry on even when we don't know all the facts

-- Conceptual complexity: Our ability to interpret the world, and choose our path among many

-- Moral ambiguity: There are almost no one-size-fits-all laws and rules. How do we make the punishment suit the crime?

-- Cultural impurity: Human culture is a mix of many influences, which can make establishing one's own identity difficult

-- Personal responsibility: Sometimes, shit happens. Sometimes, it's our fault. How do we accurately assign responsibility?

-- The confrontation of our own mortality: Death comes to us all, though we almost compulsively deny it.

We all struggle with these issues all our lives. They always demand a great deal of us; in fact, they're the questions that call us on to psychological and spiritual maturity, and the degree of wisdom we can bring to bear in answering them may be a valid measure of our overall success as human beings. But, for many who find they simply can't cope, fundamentalism offers the security of reassurance and pat answers:

Among my recovering fundie friends, we're continually confronted (and anguished) by the realization of how deeply infantilizing authoritarian culture is. Ahktar notes this, too: but he goes on to point out that the world rewards adulthood by offering much better antidotes to our existential malaise. It's only when these other, better means of coping are closed off to us that the retrogressive offerings of fundamentalism begin to look attractive.

We are at this authoritarian impasse, perhaps, because too many of the components of the package Akhtar describes are no longer available to most Americans.

Our safety -- from outsiders, from our own government, and from each other has been fraying for years, a decay that has accelerated since 9/11. This has also affected our sense of efficacy -- the ability to choose and direct our own lives and futures, and participate meaningfully in our own culture -- which has been eroding for the past three decades along with our economic, educational, political, and other infrastructures. We don't feel safe; and worse, we don't feel like we can effectively do much about it.

Being American has always been an exercise in ambiguous identity -- it’s part and parcel of our God-given right to self-recreation -- but those who defined their "Americanism" as a form of racial or religious purity have been on the wrong side of history for the past 50 years, and are feeling deeply threatened as a result.

Sexuality has always been a fraught and complicated issue for this Puritan nation, and has become only more so since the advent of birth control and women's emergence into the workplace. Our assumptions around generativity have been in flux as well: questions about who breeds, and why, and when, and how form the common thread that runs through all our culture-war conversations about abortion, gay rights, and even immigration. Parents of all political and religious persuasions will tell you America is a hard and hostile place to be raising children these days; and also of their general unease and impotence when it comes to their ability to transmit the culture and values they'd like to see carried on.

We will not, Akhtar suggests, roll back the raging fundamentalist horde anywhere until we restore a cultural climate in which most individuals can feel safe, effective and capable, strong in their personal identities, free to express their sexuality in healthy ways, and supported in their efforts to build and sustain families. When most people have access to these assets, they do not feel nearly as drawn to authoritarian religion and politics. His point seems to match up well with what we know of healthy societies -- including our own, in better decades. And it offers some essential, concrete criteria we can use to build both foreign and domestic policies that will discourage people from embracing authoritarian religion and politics, and remain strong in their desire and capacity for democratic self-rule.

Sometimes our random wanders around the Web can turn up some pretty exotic gems. This one ranks among the sparklier baubles I've found stuck in the strands this year.

It's a 2005 article by Dr. Salman Akhtar, a professor of psychiatry at the University of Delhi who's also (quite clearly) a capable and insightful philosopher. In the article, he lays out his understandings of why people turn to fundamentalism -- though his conclusions are probably extensible to most other forms of authoritarianism as well.

"Sanity," says Akhtar, "has its own burdens, and fundamentalism is the treatment for those burdens." His argument spins on six specific burdens of sanity:

-- Factual uncertainty: the need to carry on even when we don't know all the facts

-- Conceptual complexity: Our ability to interpret the world, and choose our path among many

-- Moral ambiguity: There are almost no one-size-fits-all laws and rules. How do we make the punishment suit the crime?

-- Cultural impurity: Human culture is a mix of many influences, which can make establishing one's own identity difficult

-- Personal responsibility: Sometimes, shit happens. Sometimes, it's our fault. How do we accurately assign responsibility?

-- The confrontation of our own mortality: Death comes to us all, though we almost compulsively deny it.

We all struggle with these issues all our lives. They always demand a great deal of us; in fact, they're the questions that call us on to psychological and spiritual maturity, and the degree of wisdom we can bring to bear in answering them may be a valid measure of our overall success as human beings. But, for many who find they simply can't cope, fundamentalism offers the security of reassurance and pat answers:

Fundamentalism, in a literal, narrow, ethnocentric and megalomanic manner takes a religious tract and interprets this in an extremely narrow, megalomanic and grandiose way, seeking to offer a world of simplicity, lack of personal responsibility, immortality, purity and simplicity. These are notions of children. This is how two-year-old and three-year-old children think. This is not how a grown-up, adult person thinks. Fundamentalism turns us from adults into children, turns us from individual units of flesh, psyche and spirit, thinking, pulsating, changing, constantly struggling with choices, decisions, tragedies, losses, mishaps, triumphs and victories – constantly in conflict, constantly in the inner Kurukshetra. Fundamentalism removes us from such war, from such complexity, from personal responsibility, from impurity, from handling looking death right up front in the eyes and then adopting to live in a more responsible manner.

Fundamentalism lulls us into a sleep of childhood, a sleep of simplicity but it is worse than childhood because a child is always questioning and attempting to come out of its innocence bit by bit. Fundamentalism is worse than childhood because it takes us backward, not forward. And with fundamentalism comes its twin sister, prejudice, and its evil brother called violence.

Among my recovering fundie friends, we're continually confronted (and anguished) by the realization of how deeply infantilizing authoritarian culture is. Ahktar notes this, too: but he goes on to point out that the world rewards adulthood by offering much better antidotes to our existential malaise. It's only when these other, better means of coping are closed off to us that the retrogressive offerings of fundamentalism begin to look attractive.

Efficacy, safety, identity – everybody wants to know who they are and are proud of who they are. Suppose your name is Pradeep Saxena and I ask you who’s Pradeep, you say me; I ask you who’s Saxena, that’s your father. Identity has to do with our selves and our sense of belonging to some place. We have to make sure that people are able to maintain their identities and their identities are not threatened. If they have safety, if they have efficacy, if they have identity, if they have opportunities for sexual pleasure and if they have opportunities for generativity or passing on, cultivating, elaborating their myths, language, symbols and rituals and imparting them to the next Orphic generation in a safe, tender, protective and loving way.

If we can restore this package – safety, efficacy, identity, sexuality and generativity – when it is really threatened, or when there is a manufactured threat to it, if we can prove in dialogue, by political discourse, that there is no such threat, then this package can come alive. And when compensating factors are in place then human beings are able to bear the burdens of sanity. And although burdened with sanity they then live life in more peaceful ways – peace outside and peace inside. And when they have peace inside, this is a mixture, a product of post-burdened sense, post-mourning sense, post-realisation that life is complex, difficult, limited and hybrid. When they have an inner peace, and when they know that even this peace that we have is fragile, it comes and goes, then that peace anchors them more solidly in reality and takes them away from dreams, poisonous dreams and dangerous dreams especially.

They grow up, they can tolerate other people and they can tolerate differences. They can even learn from differences and enjoy differences. They know life is limited, they know life is complex; they know that there is no moral certainty. And it is when they live with this attitude that they do not require hate because they don’t hate themselves and they do not need to hate others. And when they don’t need to hate others, they do not need to idealise themselves. And when they do not need to idealise themselves and take this intravenous morphine that fundamentalism offers them then they walk out wide awake, open-armed and with a good and clean heart.

We are at this authoritarian impasse, perhaps, because too many of the components of the package Akhtar describes are no longer available to most Americans.

Our safety -- from outsiders, from our own government, and from each other has been fraying for years, a decay that has accelerated since 9/11. This has also affected our sense of efficacy -- the ability to choose and direct our own lives and futures, and participate meaningfully in our own culture -- which has been eroding for the past three decades along with our economic, educational, political, and other infrastructures. We don't feel safe; and worse, we don't feel like we can effectively do much about it.

Being American has always been an exercise in ambiguous identity -- it’s part and parcel of our God-given right to self-recreation -- but those who defined their "Americanism" as a form of racial or religious purity have been on the wrong side of history for the past 50 years, and are feeling deeply threatened as a result.

Sexuality has always been a fraught and complicated issue for this Puritan nation, and has become only more so since the advent of birth control and women's emergence into the workplace. Our assumptions around generativity have been in flux as well: questions about who breeds, and why, and when, and how form the common thread that runs through all our culture-war conversations about abortion, gay rights, and even immigration. Parents of all political and religious persuasions will tell you America is a hard and hostile place to be raising children these days; and also of their general unease and impotence when it comes to their ability to transmit the culture and values they'd like to see carried on.

We will not, Akhtar suggests, roll back the raging fundamentalist horde anywhere until we restore a cultural climate in which most individuals can feel safe, effective and capable, strong in their personal identities, free to express their sexuality in healthy ways, and supported in their efforts to build and sustain families. When most people have access to these assets, they do not feel nearly as drawn to authoritarian religion and politics. His point seems to match up well with what we know of healthy societies -- including our own, in better decades. And it offers some essential, concrete criteria we can use to build both foreign and domestic policies that will discourage people from embracing authoritarian religion and politics, and remain strong in their desire and capacity for democratic self-rule.

Monday, October 16, 2006

Happy birthday

... to me. I was born fifty years ago today. Old Fartdom is officially upon me. Aaiiieee!!!

Well, not to be cliched about it, but it does beat the alternative.

While I'm making personal announcements, I should mention that my most recent book, Strawberry Days: How Internment Destroyed a Japanese American Community, was one of four finalists for the 2005 Washington State Book Awards in the History/Biography category. Alas, the winner was Timothy Egan's excellent The Worst Hard Time: The Untold Story of Those Who Survived the Great American Dust Bowl. My co-finalists were Jack Hamann for On American Soil and Eric Scigliano for Michelangelo's Mountain.

While I'm making personal announcements, I should mention that my most recent book, Strawberry Days: How Internment Destroyed a Japanese American Community, was one of four finalists for the 2005 Washington State Book Awards in the History/Biography category. Alas, the winner was Timothy Egan's excellent The Worst Hard Time: The Untold Story of Those Who Survived the Great American Dust Bowl. My co-finalists were Jack Hamann for On American Soil and Eric Scigliano for Michelangelo's Mountain.

I can't seem to avoid the cliches, but I am genuinely honored that Strawberry Days was deemed worthy of such esteemed company.

Well, not to be cliched about it, but it does beat the alternative.

While I'm making personal announcements, I should mention that my most recent book, Strawberry Days: How Internment Destroyed a Japanese American Community, was one of four finalists for the 2005 Washington State Book Awards in the History/Biography category. Alas, the winner was Timothy Egan's excellent The Worst Hard Time: The Untold Story of Those Who Survived the Great American Dust Bowl. My co-finalists were Jack Hamann for On American Soil and Eric Scigliano for Michelangelo's Mountain.

While I'm making personal announcements, I should mention that my most recent book, Strawberry Days: How Internment Destroyed a Japanese American Community, was one of four finalists for the 2005 Washington State Book Awards in the History/Biography category. Alas, the winner was Timothy Egan's excellent The Worst Hard Time: The Untold Story of Those Who Survived the Great American Dust Bowl. My co-finalists were Jack Hamann for On American Soil and Eric Scigliano for Michelangelo's Mountain.I can't seem to avoid the cliches, but I am genuinely honored that Strawberry Days was deemed worthy of such esteemed company.

Unacceptable indeed

The Bush administration and its defenders -- lost in the Bizarro Universe they have created for themselves -- have been using words like "incomprehensible" and "inconceivable" to explain away incontrovertible evidence of their malfeasance and incompetence.

These are fairly benign words, though, that indicate at best a kind of naivete but at worst (and most likely) a self-absorbed obtuseness bordering on stupidity.

But the president himself has been using a word with genuinely sinister connotations: "unacceptable":

- In speeches, statements and news conferences this year, the president has repeatedly declared a range of problems "unacceptable," including rising health costs, immigrants who live outside the law, North Korea's claimed nuclear test, genocide in Sudan and Iran's nuclear ambitions.

Even more remarkably, he used the word to describe Colin Powell's criticism of Bush's military tribunals.

The word turned up again this weekend, this time in the context of a Kafkaesque case of an American citizen being sentenced to death by an Iraqi judge on the mere say-so of American government officials whose behavior was nothing short of outrageous:

- Lawyers for an American citizen facing execution in Iraq appealed Friday in U.S. federal court to keep the man in American custody -- preventing his death -- while another case is being appealed.

The citizen, Mohammad Munaf, was convicted and sentenced to death by an Iraqi judge earlier this week on charges he helped in the 2005 kidnapping of three Romanian journalists in Baghdad, court papers show.

Iraqi-born Munaf, a naturalized U.S. citizen since 2000, was working as their translator and guide. He maintains his innocence.

In an emergency request filed Friday in U.S. District Court in Washington, Munaf's attorneys claim his rights to a fair trial in Iraq were violated when he was convicted without being able to present evidence in his defense -- or to see the evidence against him.

"This court's failure to temporarily halt Mr. Munaf's transfer to Iraqi custody will not only send Mr. Munaf to his death without due process, it will eviscerate ... core protections against arbitrary and lawless executive action," Munaf's attorneys wrote.

Scott Horton at Balkinization looked into the matter and found this:

- Yesterday afternoon I spoke with one of Munaf's American lawyers, and in the evening I discussed the case with one of the Iraqi lawyers who handled it. The judge, he said, had at a prior hearing informed defense counsel that he had reviewed the entire file and had reached a decision to dismiss the charges. "There is no material evidence against your client," he was quoted as stating. When two US officers appeared at the trial date with the prisoner, they reacted with anger when told of the Court's decision -- and made clear it was "unacceptable." One of these US officers purported to speak on behalf of the Romanian Embassy, which, he said "demanded the death penalty." (The Government of Romania has since stated both that it had no authorized representative at the hearing and that it did not demand the death penalty). They then insisted upon and got an ex parte meeting with the judge - from which the defendant and his lawyers were excluded. Afterwards an ashen-faced judge emerged, returned to his court and proceeded to sentence the American to death. No evidence was taken; no trial was conducted. The sentence was entered on the basis of a demand by the two American officers that their fellow countryman be put to death.

A couple of weeks ago, when Bush called Powell's criticism "unacceptable," Keith Olbermann lit into the president with all the outrage this kind of talk deserves:

- Some will think that our actions at Abu Ghraib, or in Guantanamo, or in secret prisons in Eastern Europe, are all too comparable to the actions of the extremists.

Some will think that there is no similarity, or, if there is one, it is to the slightest and most unavoidable of degrees.

What all of us will agree on, is that we have the right -- we have the duty -- to think about the comparison.

And, most importantly, that the other guy, whose opinion about this we cannot fathom, has exactly the same right as we do: to think -- and say -- what his mind and his heart and his conscience tell him, is right.

All of us agree about that.

Except, it seems, this President.

The problem with a government whose officials -- led by the president himself -- are in the business of declaring what is "unacceptable" goes deeper, I think, than just speech issues.

It's a word used by totalitarians, an arrogation of power unto themselves. A president, or his military, who can make life-and-death decisions based on what they deem acceptable or not is an executive branch wildly out of control, living in a fantasy world of their own making. And dragging the rest of us into their abyss.

Sunday, October 15, 2006

Sara's Sunday Rant: The Culture of Planning, Part I

by Sara Robinson

Watching Dave unload on Condi Rice in the post just below brought to mind another one of the timeless quotes for which she will be long remembered:

"I don't think anybody could have predicted that these people would take an airplane and slam it into the World Trade Center, take another one and slam it into the Pentagon; that they would try to use an airplane as a missile, a hijacked airplane as a missile." (May, 2002).

Brad DeLong once said that "'Nobody could have foreseen ______________' is the Bush administration version of 'The dog ate my homework.'" It does seem to be their handy-dandy all-purpose explanation for disasters that happen on their watch. We heard it after Katrina, when W got up in front of the country and said, "I don't think anybody anticipated the breech of the levees." You’d think that after the coast-to-coast derision that followed when everybody from the City of New Orleans to the Army Corps of Engineers revealed they'd seen this one coming for decades, they'd have gotten the hint and ditched this as a losing talking point. But, instead, they apparently clung to the hope that the third time might be the charm. So, when Hamas seized power in Lebanon early this year, Condi was out there once again: "I’ve asked why nobody saw it coming. It does say something about us not having a good enough pulse."

Moving to Canada has given me a fresh appreciation for what I've come to think of as America's "culture of planning." That's not a slam on Canada: when you've got just 33 million people sharing the second-largest country in the world -- and more of just about every resource than you can even imagine there ever being a use for -- there's just not a lot of need to be very organized or think very far ahead. More to the point, Canadians have never been called on to fight wars, run industries, or build infrastructure on the kind of scale Americans have, so the skill set isn't embedded in the Canadian culture to nearly the same degree.

There is a major north-south bridge (it's the Golden Gate's green baby sister, built by the same foundry at the same time) a few miles from my house, which links our far shore to Vancouver's downtown. This bridge's northern end comes to ground just 500 yards south of the city's one and only freeway, which runs east-west. Every afternoon, 50,000 homebound commuters come off the bridge and are dumped onto surface streets, causing total gridlock in our local downtown shopping district as they pass through on their way to the freeway (which is, for many, the only route out to the residential ends of town). This has been going on every weekday for 40 years -- because apparently, it never occurred to the traffic planners who built the freeway that they should cover those 500 yards with direct on- and off-ramps linking the region's major freeway to the region's major bridge.

When I ask my neighbors how something this bone obvious failed to happen, and why nobody's added the missing ramps in the decades since, they just look at me oddly. It's apparently a question that only an American would even think to ask. But, then, coming from a long line of Scots engineers, I'm a generational member of the culture of planning.

Another example. One of the most popular tourist towns on Vancouver Island was fully booked up this past Labor Day weekend. With just three days left to go before the hordes descended, their reservoir went dry. They'd known for 20 years they needed a new one, but never quite got around to building it. They'd watched it dwindle all summer, but never quite got around to matching up the remaining acre-feet against the anticipated number of users and the remaining days in the season. At the last minute, they brought in truckloads of water to tide them over, and you can bet they're planning new water storage now -- but this seems to be how planning gets done here. They react to events as they happen, rather than proactively trying to forsee what the needs will be years ahead of time.

You almost never hear stories like this in the US. Almost every county and region in the country, and every state and government agency involved in land use and infrastructure, has a regional master plan on file somewhere. Planning commissions large and small are already working 20 years out, penciling in where the major roads will go, where the water will come from, where the houses and shopping centers will be, how many schools and firehouses and sewer plants they're going to need, and how they're going to finance it all. When's your road up to be re-paved again? Odds are that City Hall can tell you, up to 10 years out.

Most of these institutions have been doing planning at this range since shortly after WWII, which was when the American culture of planning really took root. The basic tools for large-scale forecasting had been evolving since the late 1800s, accelerating with the Soviet five-year plans (the first of which famously took four years to write, largely because they were developing an entirely new set of planning tools along the way), and the awesome advances developed by the meticulously-planned Nazi war machine.

Allied generals -- most notably Hap Arnold -- realized early on that defeating the Nazis meant we'd have to become even better organizers than they were. The Allies had a massive resource advantage -- but victory in a two-front war demanded close planning to fully leverage that advantage. To this end, Arnold brought together the first teams that pioneered the field of operations research (which, after the war, formed the core founding group of RAND Corporation, which has continued to play a leading role in developing foresight techniques). This is where the American culture of planning really began.

From there, it spread. The vast industrial planning that rationed strategic resources, the factories that put Liberty ships to sea and B-17s in the air, the logistical infrastructure that moved supplies from the farms to the front lines, and the company supply sergeants who kept track of thousands of items taught an entire generation to take the long view, think in big pictures, and visualize the concrete steps that would give them greater control of future events. When the war ended, millions of men and women brought those skills home to the cities and suburbs, and applied them every aspect of their lives, from building companies to running households.

In the generations that followed, these skills and habits became an embedded part of American culture. The US was always a place where people could re-create themselves and seize new futures; but this sharp new set of tools allowed us to pursue that trait with a vengeance. From the interstate highway system to the space program to DARPA and the Office of Technology Assessment, we became a nation of planners. It's become a peculiarity of our character, this brash and pragmatic assumption that if you want to create a certain kind of future, you simply articulate the vision and start laying out the steps that will get you there. There aren't that many cultures in the world that offer such strong support for big visions, elaborate logistical and organizational planning, and long-term foresight -- yet, until you're outside America for a while, it's hard to notice how special this trait really is, or how strongly it defines us as a people.

Which is why this whole "Who could have foreseen it?" question reveals so much about what's gone wrong in Bush's America. It's an admission of yet another secret piece of the right-wing agenda that's been quietly, steadily moving along since the Reagan years, and has finally come to the point where its catastrophic implications for all of us can no longer be ignored.

For many of us, the furious response to "Who could have foreseen it?" is "How could we have screwed it up so badly? Can't we do anything right any more?" We have the sinking feeling that, even in their youth, our grandparents would have been far more likely to do the right thing in response to almost any situation -- 9/11, Katrina, Saddam, or Korean nukes are just a few -- than anybody currently on the scene now. I'd argue that this helplessness, this total inability for a nation of planners to mount an effective response to even small challenges, has deep roots in 25 years of right-wing anti-government corporatism. Because that's who's reaping the major benefits of our devastating inability to envision, organize, and implement any kind of public plan.

Futurists proceed from the premise that the future belongs to those who plan for it. If you are clear on what your vision for the future is, have a solid and accurate roadmap for how to get there, and have thought through how you're likely to deal with even the most unexpected occurrences that may upset your plans, the odds are good that you are, indeed, going to end up somewhere reasonably near your original goal. This works if you're planning for the next 60 minutes, or for the next 60 years. In short: Foresight is power. Organization and planning create the future. Those who have mastered these skills greatly increase the odds that they'll be the ones to choose the future for everyone. And there lies the problem.

Corporate leaders understand this power. (So does the religious right, which is why the largest department of strategic foresight in the country is now emerging at Pat Robertson's Regent University. They've got a vision for the future, and are getting very systematic about implementing it.) Their ability to take over the government depended on their ability to short-circuit government's capacity to exercise any kind of planning or foresight (or, importantly, oversight) on behalf of the people. The War on Science that Chris Mooney so amply documents was accompanied, in a much lower key, by a War on Planning that gutted all the various methods the government used to develop large-scale plans, track leading indicators, and detect and adjust for disruptions.

And so it was that the thousands of public employees around the country who kept track of trends in labor, public health, ecosystems, water, soil, weather, and so on just sort of went away -- defunded or discouraged at the behest of business patrons whose status quo was threatened by the statistical trends and emerging indicators these observers recorded. The engineers responsible for maintaining our existing infrastructure and planning future improvements were pushed to retire, or found jobs in the private sector. The land use commissions who enforced long-term regional plans were considered just another government obstacle to building strip malls and big box stores, and either bought off or sued into compliance. The massive strategic and logistical efforts that supported the military were outsourced to Halliburton. The accountants who might have totted up the extra costs these changed inflicted on taxpayers (though they were almost universally sold as money-saving efficiency measures) were dismissed, either metaphorically or literally.

Silicon Valley -- which through 50 years of careful investment had become the largest economic engine the world had ever seen, and was our ace in the hole for maintaining American technological dominance in this new century -- was systematically dismantled and offshored because the free-market fundamentalists regarded any kind of governmentally-directed industrial policy (which might have prevented this loss) as heresy. Even Congress, which had relied since 1972 on the impartial, first-rate analyses of its science and technology planners at the Office of Technology Assessment, bagged the agency in a 1995 budget fight, leaving itself at the mercy of whatever self-serving data the proponents or opponents of various legislation could conjure.

In short, everybody who knew how to do anything -- and especially those doing it in the interest of the people of the United States, rather than for the benefit of one or another corporate profiteer -- was gradually cut out of the process. Ridiculed and belittled as "the bureaucracy," these people had once been the eyes and ears of our common interest. For fifty years, they'd developed and maintained our visions of a future that included clean water and food, immunized kids and effective epidemic response, safe roads and buildings (and levees), good relationships with the world's other nations, and (in more recent years) responsible environmental stewardship. They monitored leading indicators, tended the engines of our prosperity, and looked ahead to the changes that would be required to keep America competitive.

And now they are gone. "Where do we want to be in 20 years?" has been replaced with "I want it NOW." Decisions based on sound science and good planning practices have been replaced with messages from George Bush's gut. On one level, this may also be a manifestation of the id- and ideology-driven self-centeredness that the Boomers have been noted for (and which will become the subject of its own rant in the near future) accelerated and expanded as they reach their latter years and assume power. But, either way, the results of this are now undeniable.

On a practical level, the losses are now manifest. On 9/11, in New Orleans, in Iraq, in the diplomatic failures that led this week to North Korea's new nukes, in the debacles around a Homeland Security department that was apparently designed for theatrical impact rather than actually securing the homeland -- this is what happens when you put government in the hands of people who believe that the only use for government is to arbitrage it (and they can't even get that right: you're supposed to auction assets to the highest bidder, not give them away to your favorite cronies). We look, astonished, at our shattered infrastructure, and know that something has gone horribly wrong. We listen, stunned, as China -- a planning culture if there ever was one -- announces (as it did last week) that it has beat us by years in completing the national backbone for its second-generation Internet network. We feel ashamed, as we wonder where our vaunted technological greatness went.

Less tangible, but perhaps even more important, are the cultural losses. We have lost the personal skills and common resources that once empowered us to envision, advocate for, plan for, and manifest a future that expresses our best American values. For that matter, we have lost belief in the very idea of "the common good," let alone our grandparents' sunny confidence that such a good could be readily planned for and achieved. This is a tragic loss. When we've finally lost our ability to dream big dreams, the skill to create the solid plans that bring those dreams into being, and our trust in each other, we have lost our entire future -- for these are the things that our shared future is made of. If we can't muster these resources and recover those losses soon -- very soon -- we will be the first Americans since the First Americans to live in a future of someone else's making.