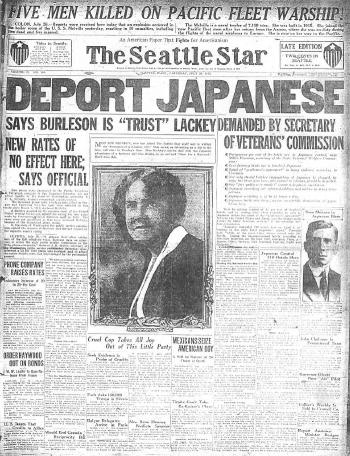

[The front page of the Seattle Star, July 26, 1919. That's Miller Freeman on the right.]

[Warning: This is a ridiculously long post. But I hope you find it interesting anyway.]

CPO Sparkey, meet your ideological forebear: Miller Freeman.

Sparkey, writing at the blog of Sgt. Stryker, has been working feverishly to justify the internment of Japanese-Americans during World War II. Most of these arguments, of course, appear to be in the service of the growing conservative tide to at least preserve the option to do the same thing to Muslim-Americans in the wake of Sept. 11.

Notably, Sparkey has been making the patently ridiculous argument that race wasn't a major concern of Americans in 1942. It was, of course -- just not in the way it is today. Instead, race was a major concern voiced mostly by white bigots who were focused on maintaining the lily-white "purity" of American culture. [See my previous post on this subject.]

Moreover, Sparkey argues, the internment occurred not because of racism, but because of legitimate "national security" concerns. What doesn't seem to occur to him is that these concerns were inextricably bound up with deeply entrenched racist beliefs.

In support of his position, Sparkey has argued the following:

- Unlike the attitudes towards the Black Americans, whose slavery was justified on the reed of racial superiority, the attitudes held by most pre-war Americans toward the Japanese was different. In talking to many of my parents' generation and reading what I have, the prejudice the average American felt wasn't racist in that the Japanese were inferior, but just the opposite, seeing the Japanese as a very capable resourceful people that looked different, behaved different, and believed different.

This argument has a more-than-familiar ring to it. Indeed, Sparkey is reproducing almost exactly the attitudes voiced at the time -- and as logic goes, it could not be more hollow.

The most vivid example of this can be found in the arguments offered by a gentleman named Miller Freeman, who was one of the founding fathers of what is now the large Seattle suburb of Bellevue, and one of the most influential Republicans of his time in Washington state.

Freeman was probably the foremost agitator in Washington against Japanese immigration from early on, beginning in about 1908, and he remained that way until his death in 1956. He was the founder of the Anti-Japanese League of Washington; he led the fight to pass the state's anti-Japanese Alien Land Laws in 1921; and he was, of course, one of the leading proponents of internment in 1942. He also happened to be an old friend of Lt. Gen. John L. DeWitt, the Western Command general who was the person primarily responsible for the internment.

Here’s a passage from my forthcoming book, Strawberry Days: The Rise and Fall of the Bellevue Japanese-American Community:

- There was one central reason why Freeman saw Japanese immigrants as a greater threat than any other: the "Yellow Peril." Like many of his contemporaries, Freeman ardently adopted a conspiracy theory holding that the Japanese emperor intended to invade the Pacific Coast, and that he was sending these immigrants to American shores as shock troops to prepare the way for just such a military action. As his counterpart in California, James Phelan, put it in 1907, the Japanese immigrants represented an "enemy within our gates." Freeman frequently cited a 1909 book promoting this theory, Homer Lea's The Valor of Ignorance, which detailed the invasion to come and its aftermath.

Freeman saw the rising rivalry over Alaska’s salmon fishery as an early salvo in this coming war. He declared in the pages of Pacific Fisherman: "If we follow the false doctrines preached by the pro-Japanese press, we will soon be making Japan a present of the Pacific Coast in order to preserve our friendly relations and build up a large American-Japanese commerce for Nippon steamships to handle."

Driven by fears of an invasion, Freeman's career soon moved into a military phase. After reading a 1910 article in Harper's Weekly calling for the formation of a Naval Militia in Puget Sound, he sprang into action. Freeman contacted the Secretary of the Navy and offered to spearhead the drive to form just such a body, comprised of ships provided by the Navy and a phalanx of yachting volunteers. He organized a meeting at the Seattle Yacht Club and lined up a muster roll and sent their names off to the Navy. In short order, the state Legislature made the naval militia an official entity, and Freeman was named its commander. The Navy provided the militia with an aging, modestly seaworthy ship dubbed the Cheyenne, and Freeman spent the next several years organizing drills and preparing for the Japanese invasion.

Such an event was nearly inevitable, in Freeman's view. He warned his recruits that they should enter the naval militia fully expecting to see battle action. "I want to warn you all that a conflict of arms with Japan is highly probable," he told the Seattle Times, adding: "The safety of the nation is in the people and the people must be aroused to action if our coast is to be saved from devastation by a foreign enemy."

Freeman sturdily denied that his campaign was driven by racial animus, saying that he "harbors no enmity toward the Japanese. They are a wonderfully bright people, frugal and industrious. But they are Orientals. We are Caucasians. Oil and water do not mix."

... Despite his contentions that he had no prejudice against the Japanese, this racial separatism was a cornerstone of Freeman's argument as he presented it in the pages of the Star. He voiced it largely by sprinkling his writing and speeches with popular aphorisms: "The Japanese cannot be assimilated. Once a Japanese, always a Japanese. Our mixed marriages -- failures all -- prove this." "East is East, and West is West, and ne'er the twain shall meet." "Oil and water do not mix."

And his conclusion became a political benchmark: "It is my personal view, as a citizen, that the time has arrived for plain speech on this question. I am for a white man's Pacific coast. I am for the Japanese on their own side of the fence. I not only favor stopping all further immigration, but believe this government should approach Japan with the view to working out a gradual system of deportation of old Japanese now here."

Freeman's views were quite typical of the time. Back then, economic competition was viewed as being part and parcel of racial competition -- a contest, it must be noted, that was almost solely instigated by whites who viewed Asians with repugnance and fear. There was also a significant sexual component to this fear; much of the agitation against Japanese was couched in terms of the "protecting the purity of our wives and daughters" sort of rhetoric that was also frequently inveighed against African-Americans, and in fact was used to justify the lynching phenomenon that was occurring concurrently.

Sparkey goes on to offer the following:

- The odds are just as good that Miss Yamashita didn't even go to school with Jimmy or Teddy, but to an all-Japanese High School funded, staffed, and propagandized with Yen from Tokyo, and there was a 1 in 5 chance of her being educated in Japan. Encouraged by Tokyo, the Japanese community in the United States was insular, keeping to their own language, separate schools (or additional schools at the end of the regular school day); forming and joining a wide and varied array of clubs and associations (ranging from the notoriously pro-fascist Silver Shirt Society to the relatively benign Japanese American League); patronizing their own newspapers, stores, and businesses.

Of course, Eric Muller at Is That Legal? has already pointed out that this is just flat-out false:

- Sparkey, there were no all-Japanese high schools funded by Tokyo along the West Coast. The Nisei (American citizens of Japanese ancestry) went to the public high schools in their communities, alongside all of the other American kids in their communities of various races and ethnicities. What I think you are referring to was the after-school programs in Japanese language and culture that many Nisei attended--at which (as you would expect with kids) most Nisei learned very little Japanese language and very little Japanese culture, in just the same way as my kids learn very little Hebrew and very little about Judaism at the after-school Hebrew School program I send them to.

Indeed, Sparkey's argument again almost perfectly replicates those raised by the anti-Japanese agitators of the time, presented not only during the internment debate but also during the debates favoring the Alien Land Laws and the 1924 Asian Exclusion Act, which had no small role in eventually bringing about World War II (as I've explained previously).

Here's another explanatory excerpt from Strawberry Days:

- The Issei were also concerned about the growing gap between them and their children. Since many of the immigrants themselves had little education and were nearly helpless when it came to learning English, their first solution was to educate their children in Japanese language and culture as a way of strengthening communication as well as ties to their heritage. A Japanese language school had been started in Bellevue in 1921, but was shut down amid the Alien Land Law agitation. Though the main intent of the Issei was simply to close the language and cultural gap between themselves and their children, the schools consistently were a source of suspicion in Caucasian communities along the Pacific Coast, in no small part due to anti-Japanese propaganda claiming that the Nisei children were being indoctrinated into emperor worship and forced to swear loyalty to Japan. Those suspicions, at least in Bellevue, were utterly groundless; none of the Nisei can recall any lessons even remotely approaching such topics, other than geography and history lessons about Japan incidental to learning the language.

A second language school opened in 1925 and held at an Issei home in the Downey Hill area until 1929, when community leaders organized the first Japanese language school at a building in Medina, at 88th Avenue Northeast and Northeast 18th Street. Asaichi Tsushima was the first teacher.

Around the same time, leaders of the Japanese community began making plans to build their own center for gatherings. By 1930, they had built the Japanese Community Clubhouse at 101st Avenue Northeast and Northeast 11th Street and dedicated it in late July of 1930. It had 16-foot-high ceilings to accommodate the basketball court the builders installed as its main floor. Some 500 people, including the leading citizens of Bellevue, attended.

The language schools were consolidated at the clubhouse, which soon became the hub for the segregated community. The Seinenkai meetings were held there. And the language lessons at the schoolhouse, which initially were held only on Saturdays, were expanded to daily hour-long sessions after school.

The sessions weren't always popular with the young Nisei. Many of them, the boys especially, hated trudging the extra mile or so to the schoolhouse while all their classmates got to have the Saturdays off. And they weren't really interested in learning Japanese. They, after all, wanted to be Americans. Most of them recall being good students at regular school, but poor students in Japanese.

"I used to pack my lunch, go over there, get in fights, learn how to throw a baseball," recalls Alan Yabuki, whose parents operated a greenhouse in the Yarrow Point area. "That's what I used to do."

Tom Matsuoka did not make his children attend the Japanese school. "He says, 'I want you guys to be able to learn English, speak it well, because this is where you are going to live. Don't want to get muddled up in this' -- a lot of these people speak in mixed idioms once in awhile," recalls Ty Matsuoka.

"Oh, but those kids just go for eating lunch, that's all," says Tom now. "They don't learn nothing.They talk the English all the time back and forth, you know."

Still, Matsuoka chipped in and helped drive the teachers for the school from the ferry dock to the school, since by 1932 he had a car, which was frequently pressed into service chauffering youngsters and their mentors to and from activities of all kinds. "Mrs. Tajitsu and Mrs. Takekawa, they used to come teach at the Bellevue School on Saturday," Tom recalls. "And so they come on the ferry, and somebody have to go on the ferry and pick them up, and take them back to the ferry after the school. [But] I never sent the kids, and had nothing to do with the Japanese school."

In spite of this reality, the myths about the purposes for the school, as well as where their funding originated, persisted, and wound up playing a significant role in the debate over the internment in 1942. Proponents of rounding up the Japanese pointed to these schools as centers for indoctrination in emperor-worship and probable hotbeds of sabotage and espionage. And just as whites' economic concerns were bound up with false racial stereotypes, so now were the concerns about "national security" regarding their Japanese neighbors.

Among the foremost of these voices, of course, was Miller Freeman. He was the most prominent civic leader to step up and advocate internment during the Tolan Committee hearings in Seattle in 1942, which essentially rubber-stamped the decision already made by FDR to intern the entire Nikkei community. The presence of the schools played a major role in his arguments.

Freeman lived in Bellevue, and his activism naturally had a local angle as well. Shortly after Pearl Harbor, he organized a local committee of white civic leaders to determine what to do about all the Japanese in their midst, who comprised about 15 percent of the population and were quite visible, since they operated most of the farms in the area.

For the first meeting of this committee, Freeman summoned a group of mostly younger Nisei men to stand before the city fathers and face the music. One of the attendees later described it to me as Freeman telling them that they were going to get "the shitty end of the stick."

I reconstructed this meeting from minutes that Freeman’s secretary took at it:

- "I am coming now to certain recommendation I want to suggest to you for consideration, which in view of your own background and training you may at first find it difficult to accept or even clearly understand, but I think we should face these things frankly," Freeman said. "These are not suggestions of the committee, but of myself.

"1. You should sever all connections with the Japanese Government -- that includes disbanding any pro-Japanese organizations designed to promote the Imperial Japanese government interests. There can't be any half-and-half business -- must be 100 percent.

"2. Stop all relationships with Japanese consular representatives.

"3. Stop using the Japanese language."

Kanji Hayashi, one of the only Issei at the meeting, interrupted, trying to explain to Freeman that he misunderstood the position of the Nisei. In halting pidgin, he told the gathering that "some people have the idea some of them are under obligation to the Japanese government, but that has never existed -- they have no relations with the Japanese Consul. The first generation cannot become citizens of this country and their country (government) must look after the welfare of those people. What they did was just to take care of them."

"Let us put an end to all that," declared Freeman.

(In fact, one of the facets of the "Yellow Peril" mythology was the notion that Japanese children born in the United States were automatically given dual citizenship in Japan, and that the Emperor considered all the Nisei to be his subjects. There was only a grain of truth to this; dual citizenship was indeed granted automatically until 1924, at which time the Japanese government altered its policy, allowing Nisei to gain such status only if their parents registered their names at a Japanese consulate within two weeks of their birth.)

Freeman then continued with the remainder of his points: "Now, I think that all Japanese language school should be stopped."

"Already stopped," Kanji Hayashi volunteered.

"You have had it up to now."

"Yes."

"May I ask now," Freeman queried, "what was the purpose of running those schools and the older people requiring that the younger people go to the Japanese schools?"

"Just teach them the Japanese language, that is all," Hayashi explained. "No other purpose, I think."

"Our feeling is that they were propaganda schools to teach loyalty to the Japanese empire," Freeman said. "I think we should stop all Japanese-language newspapers and publication in this United States of America. English is the language of this country. Use English and English papers."

Tok Hirotaka piped up: "Because our parents couldn”t speak English, so they had to teach children something about Japanese."

"I am going to suggest it was the business of older people to talk English rather than Japanese," Freeman replied.

"I wish someone could have told them before, we couldn't," said an exasperated Hirotaka. "People like Mr. Hayashi -- his children never did go to Japanese school, but they (the old folks) don’t all understand English like he does; or Mr. Takano. My mother is 65 -- here 40 years, longer than she was in Japan, but she can't talk English very well. Rest of us all talk English at home, but to her I still talk Japanese."

"I suggest that in the future no longer should older Japanese insist that these young students be raised and trained in the ways of the Japanese and their language," Freeman said.

Hayashi tried to explain why the Issei found the language so hard: "Japanese language is entirely different from other nations" and it is awfully hard for people to get mastery of it."

"English language is not hard to learn," replied Freeman.

"Italian or Swedish understand English better than Japanese," said Hayashi.

It's probably worth noting, of course, that Freeman was also a major landholder and developer in the Bellevue community; and after 1942, with the Japanese removed from their farmlands, he was free to proceed with his plans to convert the town into a lily-white suburb, which is what it was, until recently.

Now, with the growth induced by the Microsoft campus next door and the phenomenal growth of the tech industry on the Eastside, it again has a significant minority population -- about 10 percent Asian.

The more things change, the more they stay the same. Bigots have always sought various means of seemingly reasonable arguments to hide their racial prejudices. But their reasoning never stands up to factual scrutiny. And unfortunately, even people who truly harbor no anti-Asian bigotry have been known to buy into their rationalizations -- though sometimes for other, perhaps equally questionable, motives.

No comments:

Post a Comment