[From Without Sanctuary]

It is no great surprise that the photos from Fallujah last week of the burned corpses of American "contractors" being strung up from a bridge while their murderers celebrated evoked all kinds of strong feelings, across a pretty broad range. Some of these -- notably Daily Kos' -- have in turn evoked extremely powerful counter-responses, and further counters to these.

Images like these always evoke real horror -- especially, for Americans, if the corpses belong to their countrymen. When that happens, the lust for revenge comes rushing alongside.

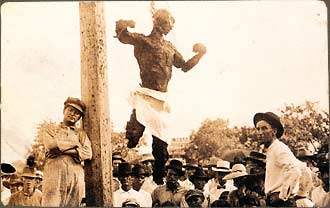

I was struck, however, by how similar these images were to those from the lynching era, when black men were routinely killed by mass mobs in the most horrifying ways imaginable -- including torturing them by flaying and dismembering them while still alive, setting them aflame, and then finally raising them aloft, often with a chain. The image above of the 1916 lynching of Jesse Washington in particular was reminiscent -- not merely for the horror of the corpse itself, but the horror of the smug satisfaction on the faces of his lynchers. This was the same horror, I think, most people felt watching those children celebrate by mutilating American corpses.

Of course, Billmon, in a marvelously insightful post, has already remarked on much the same, observing:

- I'll leave it to others to decide whether the Iraqis who celebrated the deaths of their enemies today by decorating a local bridge with their remains are worse, better or equal to the lynchers of early 20th century America, who decorated trees and streetlamps with the victims of a segregationist reign of terror. At a minimum, though, history suggests the connection between "terrorism, culture and barbaric scenes" isn't quite as tight as some of our cuture war idealogues seem to think.

Predictably, this view has been attacked as a "blame America first" mentality, which is the smear du jour for any attempt to take a thoughtful approach to what occurred in Fallujah. This is not terribly surprising, because Billmon was making a subtle point about the nature of violence that cuts deeply against the grain of jingoist reactionarism.

Perhaps the reason the pictures from Fallujah are so disturbing is that, as Billmon suggests, they hold up a mirror to us. The violence we visit readily on others is waiting to be visited on us in return; the continuously self-begetting nature of violence just spirals onward and upward.

"Bring it on," we say. The mob in Fallujah does so -- knowing full well that retribution awaits, and shouts by the horror of its act its own defiance: "Bring it on."

America the Bringer of Death is well known to Iraqis. They first encountered it in the 1991 Gulf War. They came to be on intimate terms with it during the invasions, especially the bombings. But they are not alone.

The Native Americans who populated the land first knew it well. It is hard to say where the cycle of violence began first, but by the time its spiral had completed for them, the American government had mercilessly rubbed them out.

The people of Hiroshima and Nagasaki know it well too. As did, of course, black Americans in the South.

I have discussed previously the nature of the systematic lynching of thousands of black people in America between the years 1880 and 1930.

- There are many postcards that recorded these lynchings, because the participants were rather proud of their involvement. This is clear from the postcards themselves, which frequently showed not merely the corpse of the victim but many of the mob members, whose visages ranged from grim to grinning. Sometimes, as in the Lige Daniels case, children were intentionally given front-row views. A lynching postcard from Florida in 1935, of a migrant worker named Rubin Stacy who had allegedly "threatened and frightened a white woman," shows a cluster of young girls gathered round the tree trunk, the oldest of them about 12, with a beatific expression as she gazes on his distorted features and limp body, a few feet away.

Indeed, lynchings seemed to be cause for outright celebration in the community. Residents would dress up to come watch the proceedings, and the crowds of spectators frequently grew into the thousands. Afterwards, memento-seekers would take home parts of the corpse or the rope with which the victim was hung. Sometimes body parts -- knuckles, or genitals, or the like -- would be preserved and put on public display as a warning to would-be black criminals.

That was the purported moral purpose of these demonstrations: Not only to utterly wipe out any black person merely accused of a crimes against whites, but to do it in a fashion intended to warn off future perpetrators. This was reflected in contemporary press accounts, which described the lynchings in almost uniformly laudatory terms, with the victim's guilt unquestioned, and the mob identified only as "determined men." Not surprisingly, local officials (especially local police forces) not only were complicit in many cases, but they acted in concert to keep the mob leaders anonymous; thousands of coroners' reports from lynchings merely described the victims' deaths occurring "at the hands of persons unknown." Lynchings were broadly viewed as simply a crude, but understandable and even necessary, expression of community will. This was particularly true in the South, where blacks were viewed as symbolic of the region's continuing economic and cultural oppression by the North. As an 1899 editorial in the Newnan, Georgia, Herald and Advertiser explained it: "It would be as easy to check the rise and fall of the ocean's tide as to stem the wrath of Southern men when the sacredness of our firesides and the virtue of our women are ruthlessly trodden under foot."

The lynching campaign drew on many of the nation's darker wellsprings -- particularly its taste for violence -- but it served one primary purpose, the subjugation of the black population:

- There were, of course, other components of black suppression: segregation in the schools, disenfranchisement of the black vote, and the attendant Jim Crow laws that were common throughout the South. But lynching was the linchpin in the system, because it was in effect state-supported terrorism whose stated intent was to suppress blacks and other minorities, in no small part by eliminating non-whites as competitors for economic gain. These combined to give lynching a symbolic value as a manifestation of white supremacy. The lynch mob was not merely condoned but in fact celebrated as an expression of the white community's will to keep African-Americans in their thrall. As a phrase voiced commonly in the South expressed it, lynching was a highly effective means of "keeping the niggers down."

Of course, the threat of the rape of white women and other pretenses for lynching presented handy pretexts for these horrors. As always, the violence was predicated on a fear of future violence; lynching was excused as a preemptive act.

Yet in reality a black person could be lynched for literally no reason at all -- in some cases, simply for defending himself from physical assault, or for just being in the wrong place at the wrong time. Lynching laughed at the notion of blacks advancing through hard work; moderately prosperous blacks who managed to do so were often the first targets of angry lynch mobs intent on dealing with "uppity" blacks.

And God have mercy on any black communities who tried to stand up to this violence. When this happened, the result was commonly known as a "race riot," but what these typically comprised were wholesale lethal assaults on black communities by whites. They became particularly prevalent during the "Red Summer" of 1919, when the riots broke out in some 26 American cities.

The most notable of these race riots occurred in 1921 in Tulsa, where a prosperous black population was literally bombed out of existence over two days of complete lawlessness. The rioting was set off by a black youth's alleged assault on a local white girl that later turned out to be harmless consensual contact. The youth was promptly arrested without incident, but the local press played it up with garish headlines that ignored the real nature of the incident, and one Tulsa newspaper publicly called for the young man's lynching.

This attempt, however, met with real resistance from the black community. When a group of local blacks attempted to ward off a lynch mob by meeting them at the jailhouse, the fighting broke out. Soon the entire district was swarmed over by gun-wielding whites who began mowing down black residents at random, setting fire to homes and businesses, and looting, raping and maiming. There are reports that an airplane flew over the black community and dropped incendiary bombs. By the time the violence had subsided, as many as three hundred black people were believed killed, many of them buried in a mass grave, and thirty-five city blocks lay charred. The death toll has never been properly calculated, largely because of the ways the bodies were disposed of, but some counts reach as high as 300 or more. And Tulsa's African-American community, at one time known as the "Negro Wall Street" because of its prosperousness, was never the same. Most of the survivors simply left.

We all like to think of America as a peace-loving and "civilized" nation, where freedom and justice reign supreme. But our history tells us otherwise.

And the point, of course, is not to suggest that what happened in Fallujah was some kind of response to the harm inflicted on black Americans a century ago. Rather, what it suggests is that we do not so easily escape our history by such simple distancing mechanisms as saying -- as the right is wont to do -- that hey, that happened a hundred years ago, and I didn't have anything to do with it.

The reality, however, is that there is a dark side to our preferred self-image as a beacon of hope and light to the rest of the world -- that alongside whatever democracy America has created, it has also imposed its will ruthlessly and bloodily, mainly through our seemingly endless capacity for violence. This capacity has never gone away; it has merely changed its face. In 1916, it came with rope and fire and chains. In 2004, it comes with incendiary bombing attacks delivered with the push of a button from high in the air. Either way, we produce hundreds of charred corpses, thousands of personal tragedies, and bottomless wells of hatred for our nation.

This is not to "blame America" -- it is to recognize a reality about how the rest of the world sees us, and more importantly, how the spiral of violence works. To the extent that America conducts its business with the rest of the world without resorting to violence, then we probably are a beacon of hope for democracy; but when we unleash the dogs of war -- especially when, as we have in Iraq, we do so under false pretenses -- then we open up the Pandora's Box of evil that colors both our history and our present in shades of red and black.

It's become much easier, thanks to technology, for us to indulge this violence, almost thoughtlessly. "Bring it on," says the president, with a smirk resembling those on the faces of Jesse Washington's lynchers. And his cheerleaders indulge the same arrogance of will -- vowing, as we always have, the most terrible and unending violence for anyone who dares stand in our way, or most of all, stand up to us, to threaten to visit upon us the same violence we have just visited upon them.

Justifying everything under the banner of the terrorist attacks on America on 9/11 -- attacks which, as we now know, the people of Iraq had nothing to do with -- we sit in our comfy chairs typing away on computers and urge our leaders to "nuke Fallujah," as Kathleen Parker so judiciously suggested the other day. Bill O'Reilly can broadcast to the nation his belief in a "final solution" to how we deal with Fallujah. Little Green Footballs and the Anti-Idiotartian Rottweiler likewise fulminate about leveling the city, and Instapundit nods approvingly. The ghosts of those Tulsa newspaper editors live on.

So there is no small irony in the blustering of these same right-wing bloggers over Daily Kos' remarks, particularly his callous dismissal of the fate of four contractors. If you believe, as I do, that each man's death lessens us, then there can be no condoning such sentiments. But they pale in contrast to the monstrous indifference to death that has been a major component of the "warblogger" contingent since well before the war. And it must be noted that not only is this kind of callousness out of character for Kos, he has apologized for making it -- better than could ever be said of his tormentors.

These are people who, after all, have regularly described Muslims in the most degrading terms available, often depicting them as mere vermin or, metaphorically, as diseases to be exterminated. They even sneer at the deaths of their fellow Americans, such as Rachel Corrie, if they happen to be of the wrong political persuasion. Instapundit is hardly immune from making outrageous and cruelly thoughtless remarks -- including those directed at Hispanic organizations, or soft-pedaling the internment of Japanese Americans in World War II; no one on the right, it must be noted, has ever held Reynolds accountable for this commentary.

The whole Kos dustup, in this context, is just nakedly fraudulent. Their outrage at Kos' callousness is not based on any respect for human life -- it is, as Matt Stoller makes clear, a "gotcha" game whose sole purpose is to score political points and derail the liberal blogosphere's rising influence. Kos was wrong (at least in terms of his sentiments; his factual point about the comparative treatment of American GIs was an important one to make); this does not make them right.

Particularly not when it comes to their proposed "final solution" for Fallujah, a city of 250,000, only a handful of whom participated in the recent atrocities. These acts, it should be understood, were a classic terrorist provocation, taken directly from Mao's tactics in the Chinese civil war. The entire purpose is to get American forces to overreact and take punitive action against the general populace. This turns the populace against the occupiers, making the terrorists' work that much easier, since they are no longer seen as extremists by the public but widely accepted and sympathetic freedom fighters. It also makes for fertile recruiting ground among the victims of the inevitable ensuing tragedies.

This is how the cycle of violence works, and it starts when we visit violence preemptively upon people we believe, often without real reason, threaten us. They fight back, and we visit more violence upon more of them as a way of "sending a message." And at each step, we create more hatred, and more future acts of violence. We can nuke Fallujah, sure; but when we do so, we sow the seeds for a thousand more Fallujahs, and a hundred more 9/11s.

There is another, better way, and that is to respond proportionately -- reserving retribution simply for those who committed the atrocities, and finding ways to mitigate the festering sympathy for terrorism that pervades the Iraqi countryside. We should pray, for the sake of all our souls, that our leaders in Iraq find it.

Because, as the looming civil war makes clear, their time is running very short.

Bring it on, indeed.

No comments:

Post a Comment