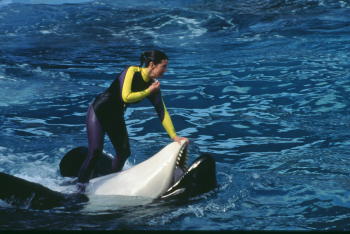

[Lolita/Tokitae at Miami Seaquarium. Photo by Kelly Balcomb-Bartok]

Until she was about seven years old, the whale called Tokitae enjoyed the life of a typical Puget Sound orca: feeding from wild salmon, playing with her family, following her mother's lead as the pod swam through its home waters.

Then, in 1970, she was among a large clan of nearly 100 orcas driven into a Whidbey Island cove by Sea World captors. Five orcas drowned in the capture, their corpses slit open and weighted down with chains to hide the evidence. The captors selected seven whales for sale to various marine parks around the world.

Tokitae was one of them; she was sold to Miami Seaquarium and shipped there in late August. They gave her the performing name of Lolita.

Since then, her life has been a steady routine of confinement in a tiny, acoustically noisy tank that is 30 percent smaller than the old Reino Aventura pool that held Keiko, the whale of "Free Willy" fame whose plight inspired a long campaign to set him free. For the first 10 years, she had the companionship of Hugo, another Puget clan orca, but since his death in 1980, she has been alone in the tank with only the companionship of dolphins and her human trainers.

A typical day for Lolita now entails entertaining the crowds who pack the aging concrete confines of the Miami Seaquarium. The paint is peeling on the underside of the benches, but crowds still come to get a splash from one of Lolita's big breaches. They really applaud when she caps off the show with a giant breach, straight out of the water, with her trainer standing astride her two pectoral fins.

She's been doing it that way for more than 25 years. Day in, day out. Her original veterinarian, the late Jesse White, described her best: "So courageous, and so gentle." Like the late Keiko, she is a charismatic animal, and a big hit with the children.

Lolita is only 32 years old. In the wild, females typically live 60 years, sometimes as long as 90. In captivity, it's quite another story: whale activists say the average lifespan of any orca, male or female, in captivity is nine years (a figure disputed by the industry).

Lolita already has beaten those odds. At 34 years, she is the second-longest-lived captive orca (Sea World's Corky, a Johnstone Strait, B.C., orca, was captured seven months before Lolita). And she is the last surviving orca from the 11 years of Puget Sound captures, which ended with a nasty lawsuit filed by the state of Washington against Sea World in 1975.

That makes her a rare -- indeed, unique -- commodity to a scientist like Ken Balcomb. His life's work has been largely devoted to documenting and monitoring the orcas of Puget Sound; indeed, the 100 or so San Juan orcas are probably the most thoroughly studied wild cetaceans in the world.

A key to understanding orcas' behavior is their unique social structure -- they organize along matriarchal lines, and speak in distinctive dialects. (Using tapes of Lolita's calls and cross-referencing them with wild orcas' calls, Balcomb in 1995 identified Lolita as a member of the Puget Sound resident orcas' L pod.) Reuniting a captive orca with her family in the wild would offer a tremendous amount of valuable information about orcas: their strictures and mores, not to mention their memories. As a relatively unpolluted female orca, she also represents potentially important reproductive stock to a population on the verge of extinction.

Balcomb wants Lolita out of her tiny, decaying tank in Miami. "We propose to retire her to a seapen here in the San Juans, where she can at least live out her days in a natural environment," he says. "And if she establishes contact with her family, and shows an inclination and ability to hunt and roam free, then we may choose to reunite her with her family. But that's far from a given."

So he and his longtime cohort (and half-brother) Howard Garrett have mounted a campaign to accomplish just that (which has now become an adjunct of the larger campaign to rescue the orcas in Puget Sound. It's not just a fly-by-night effort, either: former Washington Gov. Mike Lowry (a Democrat) and ex-Secretary of State Ralph Munro (a Republican) signed on early as supporters.

Balcomb, with his beard and tangled hair and tie-dyed shirts, may have a bit of a wild-eyed image in the stuffed-shirt circles of the aquarium industry, but he's a brilliant and widely respected scientist, and is astute about using the pull such status accords.

Political weight, on the other hand, so far hasn't been able to budge the owners of the Miami Seaquarium.

Arthur Hertz is the president of Wometco, the holding company that owns the Seaquarium and the rights to Lolita. Hertz doesn't talk to the press. And he sure as hell doesn't talk to Ken Balcomb.

His son, Andrew, recently did give an interview to the Seattle P-I's Robert McClure in a recent story about Lolita:

- "She's a member of our family, and we're not going to experiment with her just for a vocal minority," says Andrew Hertz, general manager of the theme park on Key Biscayne, just east of downtown.

The Seaquarium is a member in good standing with the Alliance of Marine Mammal Parks and Aquariums, the industry lobbying organization, which is largely sponsored by the mega-corporations such as Anheuser-Busch that operate and profit from places like Sea World. And the Alliance has made it clear for years that it opposes any of the plans suggested so far for releasing captive orcas to the wild. Not even Keiko.

"Our position on release in general, is that we do not oppose proper, scientifically based programs for returning animals to the wild that are anchored in principles of conservation biology and have the ultimate goal of sustaining marine mammal species," Marilee Keef, then-director of the Alliance, told me in 1996. "Since killer whales are not endangered, obviously release of killer whales would not have any goal of sustaining the species."

That position hasn't changed appreciably. At the FAQs on its Web site, the Alliance responds to the notion of freeing captive orcas and dolphins thus:

- The issue of releasing to the wild whales and dolphins that are currently cared for in marine life parks, aquariums, and zoos can be challenging both emotionally and scientifically. However, to experts concerned about the risks to which release exposes both the individual animal and the wild population, the issue is a simple one. Without a compelling conservation need such as sustaining a vulnerable species, release may be neither a reasoned approach nor a caring decision.

____

[Finna and Bjossa, the Vancouver Aquarium's captive orcas, in 1994. Finna died of a bacterial infection and pneumonia in 1997; Bjossa died in 2001 at Sea World from a chronic respiratory ailment.]

The unhappy outcome of the effort to "free Willy" -- which culminated in the death of Keiko from a respiratory disease he appears to have picked up in the wild -- is now Exhibit A in the Miami Seaquarium's insistence on keeping Lolita. This was mentioned prominently in the P-I piece:

- Rose says the "Free Willy" example proves his point. Keiko, the orca released in Iceland after languishing in a Mexican attraction, never did take up with other orcas, instead preferring to hang out around people. Keiko died last year in Norway. Alone.

Activists, though, point out an important difference with Lolita: Everyone knows that her family, the L pod, can be found at regular intervals in Washington's inland sea. She still "speaks" in the native "tongue" of Puget Sound orcas. Keiko, on the other hand, was set free hundreds of miles from where he was captured, where he was unlikely to encounter whales he could relate to.

Still, Rose maintains, "the similarities are greater than the differences."

The differences between Keiko and Lolita's cases run even deeper than described here. However, it's worth noting that Keiko could just as easily have died in captivity of the disease that killed him in the wild. The respiratory ailment that killed Keiko was in fact nearly indistinguishable from the similar infections that regularly kill (at far earlier ages) captive orcas -- the most notable cases, from the Northwest perspective, being the deaths of Finna and Bjossa, the Vancouver Aquarium's two captive orcas, who died in 1997 and 2001, respectively, of lung infections.

In any event, both the Seaquarium and the Alliance maintain that Lolita's situation is similar enough to Keiko's to warrant keeping her captive.

Keef said Lolita has been in captivity too long, adding that she might might carry diseases. Keef thought much of the social and language-skill information that could be gained from releasing Lolita in the wild could be just as simply obtained using telecommunications technology and hydrophones in her tank. She claimed a meeting of Alliance members even urged such a course of action.

Miami Seaquarium officials, though, have refused every opportunity to discuss such experiments. The Alliance has declined to get further involved. "It's not my business to get into the business of one of my members and what he's going to do with one of his animals," said Keef. "We don't take a position on anything like that. That’s Arthur Hertz's decision."

Hertz has refused to even discuss Lolita's sale with the Puget Sound group, though the offers so far are reportedly in the $2-3 million range. Hertz has even refused to discuss selling her to another aquarium; Vancouver Aquarium officials inquired about her availability when they were considering moving one of their own whales, but were turned down.

Hertz's strategy has been to expand his facility. The Seaquarium reportedly made $10 million in profits last year, and it wouldn't make sense for him to sell his star attraction. It's not likely a show without an orca would even come close to those kinds of figures.

But while Hertz digs in his heels, the sand is giving way beneath him. The Seaquarium itself is an aging facility badly in need of repair. As details of just how creaky the tank is have trickled out, local public pressure has risen.

Lolita's pool is the smallest for an orca in the U.S.: only 73 feet wide and 80 feet long. Its upper third is blocked by a large "work island" that the big whale slides across in her big entrance. And the sides of the pool slope out from only 12 feet of depth. The remaining living space for the 22-foot-long whale is only 68 feet wide and 34 feet deep.

Damning video footage, taken by Russ Rector of the Dolphin Freedom Foundation and played on local news stations, offered a view of the underside of Lolita's tank: a Kafkaesque maze of temporary jacks and supports, jury-rigged to keep the steadily leaking tank bottom in one piece. An algae-covered window looks out into the tank; Rector says that when he put his hand on one of these windows as Lolita did her big breach, the glass panel moved a half-inch.

Hertz has promised to improve the pool, but faces one big hitch: he can't. Not yet, anyway.

The Seaquarium is actually located on Key Biscayne, connected to the Miami mainland by bridge. Residents of the Key have clamped down on business expansions as they've tried to rein in growth and traffic problems. They fear that a business like the Seaquarium, which draws more cars across the bridge, would worsen their problems by growing.

So far, all of Hertz's requests for permits to expand anything other than his parking lot have been turned down by Dade County.

What the public campaign involving letter-writing by schoolchildren may not accomplish, however, may in the end be remedied by the harsh realities of building regulations. Hertz appears to be in a corner, since the county's Department of Planning and Development Regulation is threatening to crack down on the Seaquarium because of its growing decrepitude. At the same time, the USDA officials responsible for issuing the Seaquarium's permits may be forced soon to take a closer look at whether or not Lolita's tank even meets federal standards -- which whale advocates say it fails by a wide margin.

Hertz meanwhile has steadily promised improvements and expansions that have never come. For several years, Wometco has been in negotiations with Key Biscayne and Dade County officials for a proposal that would give Lolita a new 2.5-million-gallon tank, about the size of Keiko's luxurious former digs in Newport, Oregon.

As the Orca Network has been documenting, most of Hertz's promises have gone nowhere. Many of the details about the miserable state of the Seaquarium facility can also be found at the "parody" Web site Miami SeaPrison.

The P-I story noted that putting the law to work is proving far more successful in achieving the first objective, which is to get Lolita out of the Seaquarium:

- Now the activists are changing their approach. Mother's Day vigils and disrupting the Lolita show with bullhorns or banners have given way to getting the government on their side.

Starting last year, Fort Lauderdale, Fla., activist Russ Rector began calling in government inspectors to remedy dozens of building and electrical code violations.

Seaquarium officials say they are working diligently to correct those problems.

On the heels of the Miami-Dade County building inspectors came those from the federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration.

Rector also tried, without success, to convince the federal Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service that Lolita's tank is too small to meet regulations.

Rector, a former dolphin trainer who cuts a fearsome appearance with his black eye patch, promises more revelations in the weeks and months to come. His goal: "I'm making them hemorrhage money. ... This is not 'Free Lolita.' This is 'Close the Miami Seaquarium.' "

Were the Miami Seaquarium able to overcome the odds and build a new pool for Lolita, many of the most pressing concerns about her situation -- namely, the size and conditions of her creaky old tank -- would be answered. With the pressure off, Hertz could continue Lolita's captivity indefinitely.

However, that no longer appears to be an operative scenario. Hertz no longer discusses the options for improving Lolita's pool. All that Andrew Hertz has to say is not exactly optimistic:

- "I would not be an intelligent man if I were not planning to live without her at some point," Hertz says.

Even the people working to free her don't know how long they have. "We know that whales in captivity only live a few years," says Howard Garrett. "She's already lived far beyond what anyone could expect.

"For Lolita it's just be a matter of time. They very well could wake up one morning and find her dead. That's what usually happens to these orcas."

_____

[Keiko and his handler, Karla Corral, in Newport, Oregon, January 1996.]

Release to the wild was supposed to mean a happy ending for Keiko. In the mind's eye, the idea is almost as simple as the end of the movie: the whale, in a Herculean leap, simply jumps over a retaining wall and is free to return to his family.

The realities of reintroduction are much more complex -- as Keiko's death demonstrated.

"Releasing animals back to the wild can work," says marine biologist Greg Bossert of the Univeristy of Miami, who has studied both Keiko and Lolita and considers them "unfit" for reintroduction. "It can work quite well, if you take certain criteria and do it within those channels.

"We've been releasing manatees, since the 1970s, and we have a very high release rate when certain criteria are met. Those criteria include length of time under the care of man, whether or not there's disease transmission potential, on and on and on."

Keiko had three well-known strikes against him: his weak health, embodied in the papilloma virus that causes skin lesions around his pectoral fins; a lack of hunting skills; and language and social skills, both crucial to survival in the wild, though there was no evidence Keiko did not have them, either.

He overcame the health issues quite readily at the Oregon pool. His food consumption doubled, largely because he became more active; he also permanently shed the skin lesions from his papilloma virus infection. Once transferred to his seapen in Iceland, however, his progress slowed considerably, since he was reluctant to learn how to hunt. He never connected with any of the wild orcas who passed by, either.

Nonetheless, he was released -- some have suggested prematurely -- and he appeared to do well. He thrived in more or less open seas for nearly six weeks, then took to a Norwegian fjord where he was able to obtain human contact. It was clear he hadn't hooked up with his family. And he died suddenly in Norway from a respiratory illness that could have been contracted anywhere, including at an enclosed tank.

As the Orca Network observed:

- The only obstacle Keiko could not overcome was that of finding his family, and unfortunately, the lack of human knowledge about Atlantic orcas hampered efforts for his successful reintegration into his wild orca community. Little is known about Atlantic orcas, it is not even known whether the Icelandic and Norwegian populations are one large group or several different communities. Though recordings were made of the wild orcas, and calls similar to Keiko's calls were found, it isn't known if he ever came close to any of his relatives or to orcas that spoke the same language and dialect.

Lolita, by contrast, appears to be a better candidate for release not simply because her health is better, but because scientists have a much better handle on her home social group, which, as Keiko's case demonstrated, could prove crucial to her survival.

But she, too, faces some serious obstacles. The biggest problem for Lolita is that she has been in captivity for so long. "The issue here is you've got a whale that's been under the care of man for [34] years," says Bossert. "My goodness, she's desensitized to just about everything a wild orca would be exposed to."

Bossert speaks from years of reintroducing animals from birds to manatees: "If you look at the figures, the longer an animal stays under the care of man, the less likely it's going to be that the animal is going to be able to survive."

However, orcas and other cetaceans may be unique in their ability to adapt to challenging circumstances because of their clearly superior intelligence. Lolita -- who was, after all, captured when she was nearing adulthood, while Keiko was captured as a young calf of about a year -- could well prove to have the memory and the smarts to regain her old skills. And there's no evidence to suggest orca releases would follow the same survival trends of other lesser species.

Indeed, the argument in favor of reintroducing Lolita to her home pod got a shot in the arm last year when Canadian and American wildlife officials enjoyed a rather spectacular success in reuniting a lost calf who had been dubbed "Springer" to her family members in British Columbia water. The calf was orphaned and wandered into southern Puget Sound, well beyond the boundary where the Canadian orcas ordinarily travel. She made news by cuddling up to boaters in the West Seattle and Vashon Island areas, and many were concerned about the continued ill effects of her exposure to humans.

So federal and state officials ganged up to capture Springer, nurse her back to health, and return her to the waters near where her family was known to roam. Sure enough, she hooked up with them, established herself with them, and has positively flourished since.

Lolita obviously has a similar advantage. And while her long captivity is a big strike against her, her longevity at the same time is a sign she's well-suited to the rigors of reintroduction. "She's incredibly strong, incredibly tough," says Howard Garrett. "If she can survive that much captivity, she probably can do fine on her own."

___

[A wild orca spy-hops in Haro Strait.]

As with Keiko, a whole litany of other reasons not to release Lolita are trotted out by those in the industry: There aren't enough fish in Puget Sound. In a few years, orcas might be as unwelcome as sea lions have become. Lolita might carry some unknown disease with her from Miami, even though she's never been diagnosed with one.

All of the criteria questions raised about Lolita ignore her special status as the last survivor of the Puget Sound captures. Setting other orcas free might have a feel-good effect, but setting Lolita free might provide real scientific data, and important data at that. The potential scientific gains -- which could in fact affect the ability of researchers to sustain the dwindling population in Puget Sound -- might be considered enough to overrule concerns about sticking to standard criteria.

This is, in fact, the one significant change in the landscape that that logically may force at least the Alliance, if not the Seaquarium, to change its position at least as far as Lolita is concerned. The Puget Sound orcas are now in fact a genuinely endangered population -- and the Alliance, at least, continues to state as part of its mission support for projects that enhance their recovery.

When I first began studying orcas in the early '90s, the population of Puget Sound's reswidents was at a relatively healthy -- and seemingly steady -- 90-100 killer whales. But in the late '90s, the numbers began to decline precipitously. Now we're down to about 70 residents, which is likely the genetic-pool tipping point. If they decline much further, they will no longer have a viable population, and their eventual decline and disappearance will be written in stone.

The most recent development on this front was the news that state wildlife officials intend to put the orcas on the state's endangered-species list, event though, as I've been reporting, the Bush administration has gone out of its way to avoid giving the orcas -- or any wildlife -- ESA protection:

- The Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife proposed [March 2] that Puget Sound's orcas be added to the state's list of endangered species, citing a dramatic decline in resident whales.

Providing endangered status at the state level doesn't do as much as a federal listing -- which is being reconsidered -- but environmentalists and orca researchers hope it will help.

"The state is in the driving role when it comes to pollution-control issues and habitat restoration and habitat destruction," said Kathy Fletcher, executive director of People for Puget Sound. "The state can do a lot. This is very helpful."

"It's a good idea to list them," said David Bain, a researcher with the University of Washington who studies the effects of sonar and other noise on marine mammals. "The population is small. ... They made the right decision there."

The resident orca population once numbered about 200, but has dropped to a current estimate of 83. A shortage of salmon, their favorite food, combined with high levels of toxic substances in the orcas and harassment by overzealous whale watchers are blamed for the decline.

The National Marine Fisheries Service decided in June 2002 that the Puget Sound killer whales did not qualify for federal endangered-species protection.

In December, a U.S. District Court judge struck down that decision and ordered the agency to review its position by the end of this year. NMFS decided to protect the killer whales under the Marine Mammal Protection Act, which is less stringent than endangered-species protection.

The Canadian government already has listed the orcas as endangered.

It's difficult to say to what extent Lolita's return would help with species recovery -- though obviously, if she's still capable of bearing calves (and female orcas are known to reproduce into their 40s) simply adding her to the available genetic pool would be helpful. There may be other useful data as well, particularly regarding their behavioral patterns -- though what that data might be, of course, remains unknown.

In any event, all that's been proposed so far is to retire Lolita to a natural seapen, where she can at least live out her days in a native environment. Alliance officials have so far formulated no response to that plan, though one scientist noted that no one's applied for permits for such a project yet.

In many respects, Lolita makes a superior candidate for release, since her original family is easily located and often passes through the waters where he pen would be. Her health is good, she was older when she was captured and so is more likely to have retained hunting skills, and her history and family origins are fully detailed.

"Personally, I think she's an excellent candidate for release," says John Hall, the former Sea World research director who now advocates against captivity.

Nonetheless, the biggest obstacle for Lolita is probably the most difficult: The successful return to the wild of any orca would increase public demand on the industry to set other whales free.

"Setting Lolita free would set a precedent," says Hall. "They're terrified. They say it won't work, they're going to die, they're going to grow wings and fly to Mars, or pick another reason why it won't work.

"But if it does work, then what the hell do they say? Their credibility goes right out the window."

If it were a mere matter of public opinion, the Alliance's position wouldn't be an obstacle. But its money and influence is pervasive in the scientific community that makes the decisions and guides government policymakers. Scientists who speak out in favor of release tend not to get industry grants later.

If the outlook is bleak for killer whales ever going free, though, it is only because big money is involved. And the cash flow in the captive-orca industry is so high because the animals themselves are so popular.

The very tide of people exposed first-hand to the animals could eventually force the industry itself to change. Orcas have a way of pleading their own case by their very presence. And the public is seeing more of them, and more about them.

"I think there's some of that, where they've had the opportunity to see the animals up close and personal at Sea World or another oceanarium, and then they begin to compare and contrast what they see at Sea World with what they're seeing from documentary movies," says John Hall.

"And then, of course, the kids come home from school, where the kids are using documentaries and CDs and what not -- and I gotta tell you, they are big-time into whales. And the kids get an educational viewpoint at school, as you might expect. They don’t get, 'This Bud's for you.' "

Learning about the animals has bred an unprecedented level of respect for them, hence the desire to treat them better. Moments like the campaign to free Keiko were the first steps in that direction.

There are serious scientific questions that have to be answered before wholesale freeing of orcas could ever occur. In some cases -- especially for the captive-born -- wild release may well be out of the question.

Nonetheless, ending captivity for orcas who can be released ultimately makes sense because it is, indeed, the right thing to do. Anyone who has seen what life is like for a big, free-roaming whale in the wild knows that if they can be returned to their families, they should be.

The people who own orcas eventually will have to confront growing doubts about the wisdom of what they do.

"I've never believed these whales were put here to entertain us," says Ken Balcomb. "These whales belong to themselves, not to us. It's time we treated them that way."

No comments:

Post a Comment