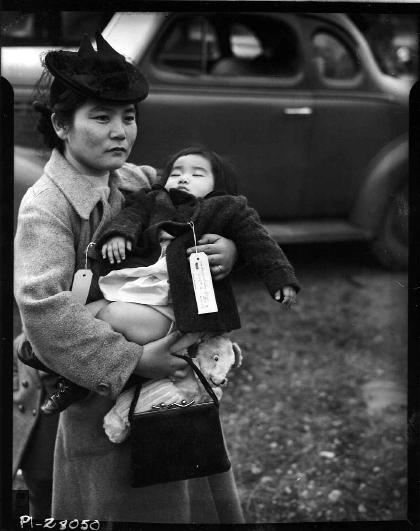

[Koyo Hayashida and her 2-year-old daughter wait to board the ferry at Bainbridge Island on March 30, 1942, en route to the concentration camp at Manzanar. Seattle Post-Intelligencer Collection, Museum of History and Industry. This photo is not a forgery.]

In her bestselling In Defense of Internment (which I have previously discussed here, here and here) Michelle Malkin extolls as among her chief qualifications for authoring such a text "the ability to view the writing of history as something other than a therapeutic indulgence."

There is no small irony in this, considering that Malkin's text is a crystalline example of "the abuse of history" (as she puts it elsewhere) as right-wing "group therapy." In Defense of Internment takes a few small slices of fact, removes them from their larger context or distorts their significance, embellishes them with non-facts, either sneeringly dismisses or utterly ignores an entire ocean of contravening evidence, and then pronounces the whole enterprise history.

That isn't history. It's propaganda.

Malkin, in fact, manipulates history in a way that makes clear that her entire methodology is little more than a polemical parlor game: Play up whatever scraps of evidence you can find to support your point, pretend that the wealth of evidence disproving your thesis simply doesn't exist, and then fend off your critics with a steady string of non-sequiturs and irrelevancies, never answering their core criticisms. This tactic is familiar to anyone who's dealt with the right much, especially in the past decade. Just call it Oxyconfabulation.

It can be an effective polemical style in terms of fooling mass audiences with little historical training or appreciation for the nuances of research, though it certainly hasn't fooled any serious historians.

What is grotesquely wrong, however, with playing parlor games with history as Malkin does is that it traduces and trivializes and rationalizes the very real injustice that was visited upon some 80,000 American citizens and some 40,000 of their longtime resident immigrant parents, whose primary reason for never gaining citizenship lay in the racist laws which prevented them from doing so.

There was real human pain and real human suffering produced by this episode, more than can ever be justified by the preposterously thin claim of "military necessity." Malkin thoughtlessly bulldozes over these people's lives, especially when she resurrects the old "A Jap is a Jap" canard by consistently clumping Nisei, Issei and Japanese spies together under the term "ethnic Japanese". More egregiously, she libels their good names by claiming, without anything resembling sound evidentiary support, that widespread suspicion of their loyalty as citizens was well-grounded. As I've mentioned before, I know some 442nd vets who would be happy to discuss this with her, since it is their loyalty she is impugning by associating them willy-nilly with Japanese consulate spies.

Unsurprisingly, her thoughtless wreckage of history is wreaking havoc in people's lives in the real world. Her book has inspired yet another right-wing maven wannabe to challenge her local school district's teaching of the subject, claiming that, contrary to the weighed judgment of hundreds of historians and legal experts, the forced incarceration of Japanese American citizens in World War II was not a mistake. And she is waving Malkin's book as "proof."

The real irony: it has happened on, of all places, Bainbridge Island.

That's right. The site of the first "test run" of the evacuation. A place where people's experience of the internment is more than a mere pedantic exercise.

Bainbridge Island's strawberry farmers were targeted that spring of 1942 by Lt. Gen. John L. DeWitt because he feared they might be providing, via shore-to-ship communications, military data to Japanese subs about the movements of American ships moving in and out of the major naval port in Bremerton, which is a visual stone's throw from the island's western side. He also feared sabotage from the same populace. Of course, the only evidence he had for these fears were second-hand anecdotes and FBI reports of raids in which Nisei were found with such items as guns and dynamite (all of which, of course, were stock items for rural Washington farmers, who often hunted and whose work always entailed stump removal, which usually entailed explosives).

So Bainbridge Island was first on his list, and on March 30, 1942, Army personnel -- under the direction of Col. Karl Bendetsen, architect of the internment -- showed up on the island and escorted 276 Nisei and Issei from their homes, boarded them onto the ferry, and took them to Seattle, where they boarded a train that took them directly to Manzanar, California, where the first of the internment camps had been erected.

The Bainbridge evacuation went off so smoothly, in fact, that the government quickly realized that pulling off evacuation on a massive scale was possible, and proceeded apace.

But the evacuation was never popular on the island, because the Japanese had been there since the turn of the century, and they had long-established roots in the community. Their kids went to school with the Caucasian (mostly Scandinavian) population, and they played baseball together and looked out for each other as all neighbors do. Most of the island's residents were shocked, and on the morning they departed, many of them turned out to watch and were appalled.

The legacy of that knowledge is imbedded deeply on Bainbridge. The island's most famous current resident, author David Guterson, is best known for his novel about the internment tragedy, Snow Falling on Cedars. Many internees and their neighbors, as well as their descendants, still make Bainbridge their home. In recent years, the island has been swamped by newcomers, but the long-established families still are a powerful presence in the life of the community.

So when a local mother, one of the relatively recent arrivals, who had read Malkin's book -- and, like most of the wannabe internment "experts" who have popped up on the Web, apparently little else about the internment -- decided to challenge the local schools' curriculum in teaching about the episode, it didn't go over very well.

As the Seattle Times reported:

- Dombrowski, in her brown jeans and linen shirt and almost-clogs, has that artsy/graduate-student look, particularly with a satchel draped across her back. The satchel is stuffed with letters to the school district, letters written back to her, a paperback written by Lillian Baker titled "American and Japanese Relocation in World War II: Fact, Fiction & Fallacy."

The book is controversial, as is a new book by Michelle Malkin, a former Seattle Times editorial writer, that defends the internment. Malkin's arguments have fueled Dombrowski's resolve that the internment is a complex, nuanced historical event and that the subject ought to be presented as such.

... At Sakai Intermediate School, named after local internee Sonoji Sakai, Principal Vander Stoep acknowledged the internment is presented with one point of view.

"We do teach it as a mistake," she said, noting that the U.S. government has admitted it was wrong. "As an educator, there are some things that we can say aren't debatable anymore." Slavery, for example. Or the internment -- as opposed to a subject such as global warming, she said.

Thursday night, the Bainbridge school board made clear it had no intention of backing down, as The Sun reported:

- A curriculum for Sakai Intermediate School sixth-graders about the internment of Japanese-Americans during World War II was debated for about an hour and 20 minutes at Thursday's meeting of the Bainbridge Island School Board.

The night was civil, with most of the about two dozen speakers coming down in favor of the board's decision to continue teaching that the internment was a mistake.

The curriculum had its first run in February after its development by former sixth-grade social studies teacher Marie Marrs. The district received a $17,000 grant from the Washington Civil Liberties Education Program to offer the program to Sakai sixth-graders

Bruce Weiland, school board president, prefaced the discussion by saying the district's position, including some changes, had already been made.

-- The program would probably be shortened from the month it took last year to teach it.

-- A call for more historical context would be considered.

-- Linking the internment with modern issues would be done with care. Weiland said it's not the school's role to tell students whether the Patriot Act is good or bad.

-- The basic point, that the internment was a mistake, was illegal and a tragedy remains the same, Weiland said.

The Sun also carried a photo from the meeting that caught my interest:

Both of these men are 81. The man on the right is Jerry Nakata, who had graduated from Bainbridge High in 1941 and who was one of the islanders swept up in the evacuation; Nakata still lives on the island. The story quotes him briefly:

- Nakata said he was forced to leave the island March 30, 1942, because he looked like the enemy. "The only guilt I had was my face," he said.

The man on the left is a World War II veteran named Earl Hanson. He was a neighbor and childhood friend of Nakata's and graduated from high school the same year. He also was an eyewitness to the evacuation.

I had the real pleasure of interviewing Earl Hanson earlier this summer for the oral-history organization Densho. He lives in nearby Poulsbo in a home built by his wife's parents, tucked away on a hillside. He's a very charming man and a devoted partisan of all things Norwegian. He also has very strong feelings about the internment.

Hanson, you see, also fought against Japan in the Pacific Theater. He joined the Navy shortly after seeing his friends shipped off to Manzanar -- the memories of which still bring tears to his eyes -- and wound up being shipped off to fight "the Japs." He saw action at Midway and elsewhere, and endured a couple of trans-Pacific crossings in the small Navy boats to which he was assigned.

Hanson, perhaps more than the average sailor, was acutely aware of the difference between "the Japs" he was fighting and the Japanese Americans back home. And he understood that what happened to them arose from other people's -- and especially the government's -- failure to comprehend the distinction.

He especially remembers a bus trip he took, late in the war, from a training station in Colorado to his assignment in Seattle, still in uniform. En route, the bus stopped in Walla Walla, and while at the station, Hanson espied a couple of Nisei classmates, members of a family who had made their way out of the internment camps by going to work for a local farmer. Hanson got off the bus and greeted them, and they were quickly joined by the rest of the family. A brief and happy reunion ensued.

As he returned to his seat, a man near the back of the bus began talking out loud about how those "damned Japs" had no business being anywhere but behind barbed wire. Hanson -- who is a big man even now, and he must have been imposing at age 20 -- took umbrage. He stood and "gave that guy an earful," pointing out that those were friends and neighbors of his and insisting that (in the inimitable lexicon of the prewar generation) "they were every bit as white as you and me."

The rest of the bus ride to Seattle (which in those days was about eight hours), Hanson said, there was nothing but silence.

It might not be a bad idea to somehow get Earl Hanson on the same bus as Michelle Malkin, since he no doubt would give her a piece of his mind as well (though who knows how he might put it). Certainly, it would remind her that there is a real human component to the history her book attempts to trivialize.

However, there's not much likelihood it would make any difference; she has not responded well so far to even measured criticism like that of Eric Muller and Greg Robinson. Petulance and arrogance are an ugly combination, but they are probably more honest than the quasi-objective pose she affected at the outset of the discussion.

The hallmark of Malkin's response has been to ignore the core criticisms -- particularly the absence of any discussion of the role of racism and its history in a text one of whose central theses is that racism was not a proximate cause of the internment -- and to instead launch a thousand non-sequiturs, while mischaracterizing and distorting her opponents' arguments.

This is true not merely in her response to Muller and Robinson, but other critics as well. Her response to the debate on Bainbridge Island: "What are they so afraid of?"

Of course, no one is afraid of anything. But what they won't condone is the falsification of history.

My old friend and colleague Danny Westneat had a thoughtful column about this earlier this week:

- Even if you discount these 39 historians, and also ignore the moral implications of jailing innocent people, it still is indisputable in hindsight that the internment was a failure and a colossal waste of money. There just isn't any evidence it fulfilled its stated purpose, which was to catch spies and prevent acts of espionage.

That's what they are teaching the sixth-graders on Bainbridge Island -- that the internment uprooted the lives of American citizens and failed to achieve its security goals.

What's more, students explore how echoes of the internment can be found in the current war on terror, what with some people being jailed without being charged or having access to a lawyer.

Isn't this what the teaching of history is for? It's not to give equal time to all ideas, regardless of merit. It's to describe the past accurately, and then analyze it to learn why it happened and what it means today.

What Malkin (for obvious reasons) refuses to acknowledge is that, in terms of the writing of history, her work is demonstrable rubbish that simply does not withstand serious scrutiny. We don't give equal time so our children can hear from the Flat Earth Society or the defenders of slavery or the Holocaust revisionists. Demonstrably false beliefs do not rate equal time with the broad consensus of several decades' worth of factual historical research.

Unsurprisingly, Malkin has mischaracterized Westneat's argument as "that internment ought not even be debated". Of course, what he's saying is that giving fraudulent propaganda that falsifies history enough credence to present it as "just another viewpoint" -- in other words, giving falsehoods equal footing with established truth -- is not a "debate". It's a travesty. And our schools have no business exposing our kids to it.

Had Malkin attempted a serious work worthy of real debate, it would have honestly examined the role of racism as a significant if not decisive factor at nearly every crucial juncture in the unfolding process that eventually produced the internment travesty. It would have reckoned with the mountain of overwhelming evidence, produced in historical text after text, that this was the case. It would have discussed the role of the "Yellow Peril" conspiracy theories, the anti-Japanese agitation of 1912-24 that culminated in the Alien Land Laws and the Asian Exclusion Act, eugenics and the ascendance of white supremacism, and the permeation of these beliefs in nearly every level of society, including those of the key decision-makers.

If Malkin were serious about attacking the thesis that these factors were significant, she'd have produced a work that addressed that evidence and offered both counter-evidence establishing that this racism did not exist and was not present in the many rationalizations for the internment, as well as both a long-term and a proximate cause for the political pressure favoring the evacuation.

But what do we find in her text?

Nothing. Not a single word. The only time racism is mentioned is when Malkin is simply dismissing it as a cause.

Malkin has likewise airily dismissed suggestions that her work is akin to that of Holocaust revisionists, pointing to a brief passage in her book that doesn't actually address the issue, but simply discards the comparison as somehow beyond the pale. But as Eric Muller and others have observed, the comparison is quite valid when we're talking about methodology and history.

As Muller says, comparing Malkin to David Irving (as both I and Timothy Burke have done) is not to suggest that the American internment tragedy is somehow analogous to the Holocaust. What it does say is that Malkin's methodology is nearly identical to that of Holocaust deniers like Irving.

I happen to know a little about Holocaust denial, since it is a prominent feature of the neo-Nazi and Patriot right. A number of my interview subjects for In God's Country expounded on Holocaust-denial ideas, and I've also had the distinct displeasure of having waded through more than a few Holocaust-denial texts and Web sites. (I showered afterward, I promise.)

The truth is that Malkin's methodology in terms of historical analysis is identical in nearly every respect to that of Irving and his fellow deniers at places like the Institute for Historical Review and the Barnes Review.

You see, Holocaust deniers don't exactly deny that there was mass genocide directed at the Jews. But they minimize it systematically: Arguing that there weren't 6 million Jews murdered -- the number, they say, was more in the range of 100,000. Then placing it in the "broader context" of the millions of people killed by the war itself (war is hell, you know), thus suggesting that the Holocaust was an act of war and not of mass genocide. Finally, throwing up "previously undiscovered" counter-evidence -- like the claims that there were no gas chambers at Auschwitz -- that, on close inspection, proves either bogus or a gross distortion, often by omission.

For those not familiar with the milieu, David Irving remains the best and most illustrative example of this kind of approach to history. Irving, unlike Malkin, is an academically trained historian, one whose career arc traversed from "controversial" to "extremist" over the course of several years. (Malkin's arc, comparitively, is now somewhere in between.)

Even in his early, "controversial" years, careful examination of Irving's methodology revealed "that he omitted important evidence and that he misused, manipulated and even altered documents to support his theory" (sound familiar?). Eventually, rather than accept the criticism and alter his approach accordingly, Irving defiantly drifted into the murky waters of Holocaust denial:

- Until 1988 Irving refrained from supporting the deniers' outlook explicitly. The event which caused him to cross the line and join the deniers' camp was the publication of The Leuchter Report. Fred Leuchter, who claimed to be a specialist in constructing and installing execution apparatus in US prisons, was hired by the Canadian Holocaust denier Ernst Zündel to be an expert witness at his trial. Before the trial, with Zündel's financial assistance, Leuchter traveled to Poland where he visited Auschwitz, Birkenau and Majdanek and illegally collected "forensic samples" for chemical analysis. In his published findings, he claimed that the facilities in these camps were not capable of mass annihilation. The allegation that the gas chambers in Nazi concentration camps in general and in Auschwitz in particular were used only for disinfection purposes was not new, having been raised already a few years after the war by one of the first European Holocaust deniers, the French fascist Maurice Bardèche, and from then on it appeared in numerous Holocaust denial publications. For Holocaust denial writers, however, Leuchter's report was significant. It was introduced as a major breakthrough for those who were "seeking the truth"; now their claim had allegedly been proved scientifically. "For myself, shown this evidence for the first time when called as an expert witness at the Zündel trial in Toronto in April 1988, the laboratory reports were shattering. There could be no doubts as to their integrity," wrote Irving in his introduction to The Leuchter Report, which was published in the United Kingdom by Irving's publishing house Focal Point Publications.

Holocaust denial recently crossed a number of people's radars because of the controversy over Mel Gibson's The Passion and its anti-Semitic nature. Regular readers will recall that Gibson's father, Hutton Gibson, speaks at Holocaust-denial conferences and has been interviewed several times expressing such beliefs quite unmistakably.

Mel Gibson himself has referred to his father as an intellectual mentor several times, though he heatedly denies being anti-Semitic. But the denials are couched in the evasive language used by Holocaust deniers, as on the occasion when he sat for an interview with Peggy Noonan and said the following:

- "I have friends and parents of friends who have numbers on their arms. The guy who taught me Spanish was a Holocaust survivor. He worked in a concentration camp in France. Yes, of course. Atrocities happened. War is horrible. The Second World War killed tens of millions of people. Some of them were Jews in concentration camps. Many people lost their lives. In the Ukraine, several million starved to death between 1932 and 1933. During the last century, 20 million people died in the Soviet Union."

As you can see, nearly all of Gibson's "factoids" are those trotted out by the likes of David Irving and Ernst Zundel: Yes, there were many Jews killed in Europe during World War II, but they were only a small part of the total who died in the war, and the "6 million" number is grossly exaggerated. Irving himself put it this way:

- I am not familiar with any documentary evidence of any such figure as six million ... it must have been of the order of 100,000 or more, but to my mind it was certainly less than the figure which is quoted nowadays of six million ... .

In Defense of Internment is less, perhaps, David Irving and more Mel Gibson, since it lingers just short of explicit radicalism. However, it employs a methodology very similar, if not identical, to the deniers: It fudges numbers, claiming, for instance, that the numbers of Nisei serving in the Japanese Army ranged "from 1,648 ... to as high as 7,000", a range that renders it almost meaningless, while omitting the fact that many of those Nisei were unfortunate students forcibly conscripted into service. It elides whole ranges of evidence and manipulates other pieces of evidence in a way that is clearly deceptive. It rationalizes the internment by raising the canard that because many of the Nisei were technically "dual citizens," their loyalty was suspect, thereby minimizing the impact of the incarceration for thousands of loyal citizens. It tries to place the decisions that drove the internment in a false "context" of supposed military concerns about an imminent invasion (though Malkin has since conceded that the military's only real concern was about spot raids similar to those that wracked the East Coast -- where German American citizens were not incarcerated -- as well). And it raises "fresh evidence" in the form of MAGIC encrypts, the significance of which has consistently been discarded by serious historians as minimal at best, for sound factual reasons.

As the Irving example suggests, this kind of approach to history -- in which facts are mere indulgent playthings to be manipulated and distorted at will, all in the service of "proving" a thesis -- is more than a mere exercise in pedantic polemicism. It inflicts real-world harm on the lives of ordinary people by minimizing the tragedies of those who actually lived through the events whose memory they abuse so blithely.

Worst of all, in doing so, they pave the way for these tragedies to repeat themselves. And that, really, is what makes Malkin, Irving, Gibson and their like truly reprehensible.

No comments:

Post a Comment