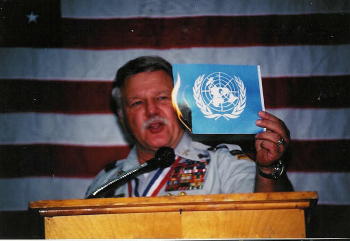

[James "Bo" Gritz at a Preparedness Expo in Puyallup, Washington, in 1998.]

Good gawd, if the Terry Schiavo drama -- and especially the atrocious role played in it by Jeb Bush -- weren't enough of a three-ring circus already, it's now drawn the participation of the extremist right. We're escalating from travesty to potential tragedy.

Namely, my old friend Bo Gritz, has leapt into the fray with a chorus of approval from World Net Daily and The Free Republic:

- Former Green Beret Commander Bo Gritz is trying to conduct a citizen's arrest of Terri Schiavo's husband and the judge who ordered the brain-damaged Florida woman's feeding tube removed so she can be legally starved.

The 66-year-old retired Army Lt. Colonel with his wife, Judy, arrived in Florida from their home in Nevada yesterday with the intent of arresting anyone involved in removing the life-sustaining tube.

Gritz came bearing a notarized "citizen's arrest warrant" addressed to Florida Gov. Jeb Bush and Attorney General Charlie Crist.

His intent is to "paper" state and federal law enforcement offices with his warrant today – one day before Pinellas Circuit Court Judge George Greer's deadline to begin denial of food and water to Terri Schiavo.

Gritz says the "arrest" is designed to allow officials additional options as the Florida governor and legislature maneuver to save the woman from starvation.

Gritz says he successfully used the arrest-tool against federal law enforcement in August 1992 when he intervened in the so-called Ruby Ridge incident in Idaho and brought what was left of Randy Weaver's family down the hill without further bloodshed. Sammy, the 14-year-old Weaver boy, was killed along with his mother, Vicki, and U.S. Marshal William Degan. Randy Weaver and another man, Kevin Harris, were wounded by police gunfire.

Er, actually, that wasn't what happened. Bo showed up at Ruby Ridge and read out his arrest warrant at the blockade. But these threats were utterly ignored. In fact, since he was present, and Weaver was a big fan of Gritz's, the FBI decided instead to see if he could negotiate an end to the standoff. And, in fact, he did. But the arrest warrants were not only a nonfactor, they were something of a joke.

Ever since then, Gritz has made a career of showing up at standoffs and other celebrated cases and touting his public reputation, but having no effect whatsoever except perhaps to make things worse. I described in Chapter 7 of In God's Country his arrival at the Freemen standoff in Montana:

- The media horde was ready and waiting for Colonel James "Bo" Gritz when he flew in to Jordan. Which, as far as Gritz seemed to be concerned, was just fine.

For that matter, possibly the most dangerous place to be that day in Montana was between Bo Gritz and a television camera. Scarcely had his light plane touched down at the Jordan airstrip before Gritz climbed out and walked out to meet the waiting newsmen. Right behind him was the man responsible for Gritz's chief claim to fame: Randy Weaver, the martyred widower of Ruby Ridge.

It had been nearly a month since the FBI's standoff with the Freemen had begun, and the situation seemingly was going nowhere, although negotiators said they were making progress. Gritz and Weaver, following through on a promise Gritz made earlier that week on his short-wave radio program, had arrived to try to broker an end to the confrontation.

It was a nasty, windblown Thursday, with gusts hitting 60 miles an hour, and Gritz's entourage seemed intent on getting out of the winds and on with the mission. Gritz held the cameras at bay, chatting briefly with the newsmen, while Weaver and Gritz's two right-hand men, Jack McLamb and Jerry Gillespie, got out of the light plane and into a large pickup. Then, saying he'd make a statement later, the onetime Green Beret colonel climbed into the truck and headed off to meet with the Freemen -- or at least try to.

Gritz was far from the first person from the Patriot movement to show up on the scene. Only two days after the standoff started, a Kansas militia activist named Stewart Waterhouse and a cohort, Barry Nelson, took advantage of the loose perimeter around the compound and sneaked onto the Clark ranch, bolstering the Freemen's numbers in the process. The FBI clamped down on activity in the area and set up a checkpoint at the four-corner intersection near the Brusett post office. The media were confined to a hill that overlooked the Clark ranch from a considerable distance.

Over the next few weeks, Jordan saw a steady trickle of militia folks come in and out of town. A small group of supporters from Medford, Oregon, took the long drive out with food supplies and a few guns, but they were stopped at the perimeter by the FBI, their guns confiscated, and turned back. Kamala Webb, a Bozeman woman who heads up a Militia of Montana group in Gallatin County, drove up with another small group, including Dan Petersen's stepson, Keven Entzel. They too had food supplies for the Freemen; they too were turned back. And then there was the occasional solitary supporter, like Bill Goehler of Marysville, California, who drove out on his Honda 750 motorcycle and demonstrated in front of the FBI checkpoint by leaning against his bike and holding an American flag upside down.

The most colorful of all the arrivals so far had been "Stormin'" Norman Olson, the onetime commander of the Michigan Militia, who visited Jordan during the third week of the standoff with his longtime sidekick, Ray Southwell. He was there to support the Freemen, he said, and to make sure the FBI didn't try to pull any fast ones.

"I don't think they should surrender," Olson said. "I think they are doing the right thing, and they ought to stay where they are."

Tension was building around the compound at that point. It was April 16, only three days away from the Oklahoma City anniversary, and many townsfolk in Jordan were growing fearful that the Patriots would descend on their town and violence would erupt. Olson only made matters worse, saying he was there to organize a "national response team" that would "meet Janet Reno and the FBI, wherever they attack in the future. Waco, Ruby Ridge, now Montana. Where is it going to end?"

Olson tried several times to enter the compound, but was rebuffed by the FBI, even when he carried a stuffed animal and a Bible and claimed he wanted to go in to "minister" to the group. Finally, on April 19, Olson gave up in disgust.

... Four days later, Bo Gritz, always more affable and media-savvy, flew in to the Jordan airstrip on his own mission: to negotiate an end to the standoff, much as he did on Ruby Ridge. After his initial bow to reporters, he and his entourage headed up the gravel road to Brusett to see if they could talk their way onto the Clark ranch.

They couldn't. At the checkpoint, a grim-faced Montana Highway Patrolman told Gritz he’d have to get clearance from the FBI. A little nonplussed, Gritz turned to the waiting news cameras and did what comes most naturally to him -- he held a press conference.

"We are going to try to do for the Freemen and FBI and the American people what we did at Ruby Ridge," he told the gathered reporters. "We don't want any more Wacos and I don't want to wait for Janet Reno to have a bad hair day to have one."

While Gritz held forth, Randy Weaver and Jerry Gillespie waited inside the pickup. Jack McLamb, on the other hand, stood outside the cluster of newspeople encircling Gritz, looking over the various lawmen who stood nearby. McLamb's specialty in the Patriot movement is recruiting policemen to the belief system; his staredown with the officers at the checkpoint had the look of someone sizing up potential believers.

Gritz spent about twenty minutes with the reporters. He told them he was unsure what standing, if any, he had with the people inside the compound. "I don't think I have any rapport at all, but I got probably the only plan.

"If the Freemen throw me out, then it gives a message to America: they don't care. If the FBI stopped me, isn't it kind of stupid? If we do bring them out, then the FBI can go home where they belong."

When he was done, Gritz got into the pickup with McLamb and headed back up the gravel road to the FBI headquarters, at the Garfield County Fairground just outside Jordan. Gritz walked in alone to talk things over with officials there; his three friends waited outside in the pickup, munching on apples and listening to Garth Brooks tapes. About an hour later, Gritz emerged, got into the pickup without a word, and drove back to the Jordan airstrip, where he had a motor home parked next to his Cessna. Evidently the FBI had said no, at least for the day.

Eventually, Gritz was allowed to negotiate with the Freemen, but it was fruitless, to no one's great surprise:

- On the fourth day, Gritz gave up, evidently in disgust. After only three hours, he and Jack McLamb left the Clark ranch no closer to a surrender than when they entered. The Freemen, he said, believed Yahweh had erected an "invisible barrier" around the compound that made them invulnerable. If the feds wanted to negotiate, they said, perhaps onetime Supreme Court nominee Robert Bork could come out to Jordan and take up residence while talks progressed. Failing that, they’d accept Chief Justice William Rehnquist. Or better yet, Colorado State Senator Charles Duke, who they said understood their beliefs.

Gritz and his entourage, wearing baffled scowls, packed up and flew out of town that afternoon. The standoff had reached 38 days with no end in sight.

Gritz's next big adventure was to get involved in the Linda Wiegand case -- involving a mother who had fled with her children as part of a custody dispute -- which wound up getting him charged with attempted kidnapping (of which he was eventually acquitted).

Then, of course, there was the whole attempted suicide thing. Bo eventually remarried, this time to a woman named Judy Kirsch, who was raised in an Oklahoma Christian Identity church.

When I knew Gritz, he worked hard to downplay his Identity involvement -- and, in fact, he had distanced himself from those associations in part because of a public dispute with the Rev. Pete Peters (the nation's leading Identity preacher) over the latter's pronouncements urging the death sentence for homosexuals. However, his marriage to Kirsch has erased much of that old reticence, though not all of it. As the ADL explained:

- Even since unreservedly accepting Christian Identity, upon his marriage to Judy Kirsch in 1999, he has avoided the bigoted language typical of that movement.

Through Kirsch, Gritz became active in Dan Gayman's Missouri-based Church of Israel, attending and speaking at its religious celebrations. The influence of Gayman and Christian Identity led Gritz to rename, and spiritualize, the Center for Action. It became the Center for Action -- Fellowship of Eternal Warriors. Pursuing his new mission, and adding a religious gloss to old themes, he "anointed" a small number of God's "Israelpeople" to "meet the increasing challenge of Satan’s globalism." He spent a year, he said, identifying a dozen "warrior-priests" who clearly "embody the strengths of God’s Israelpeople" -- including old friend Richard Flowers, Steve Kukla of the Oklahoma-based Sovereign Studios and Sheldon Robinson, co-defendant in the Weigand case. Gritz recruits new candidates on his Web site, telling readers: "Contact me if you feel that God has called you to be a spiritual warrior for these last days."

The Fellowship of Eternal Warriors represents the most thorough merger to date of Gritz's paramilitary training, opposition to the federal government and religious ardor. While he has since parted ways with the Church of Israel and Dan Gayman, his efforts to prepare for spiritual warfare remain undiminished. Gritz now attends both the Christian Identity Rose Hill Covenant Church in Oklahoma and the Inter-Continental Church of God in California, continues to promote SPIKE training, whose newest edition qualifies participants as a "Master Blaster," and runs the Center for Action. His religious beliefs remain somewhat vague, however, in part because he has not, at least publicly, articulated the racial implications of his Identity faith. Nonetheless, Gritz has upped the ante by enlisting God against the government and its supporters. He says:- I can assure you that if I was ever convinced that it was God's Will for me to commit an act of violence against the laws of our land, I would hesitate only long enough to, like Gideon, be certain. I would then do all within my power to accomplish what I felt he required of me. . . If God does call me into the Phinehas Priesthood . . . my defense will be the truth as inspired by the Messiah.

This latter reference is particularly disturbing, especially for those who've read Chapter 6 of In God's Country and understand the "Phineas Priesthood" reference. Essentially, though, the notion of the "Priesthood" is that one enters it by committing a killing of someone who has broken "God's law"; it is easily the most radical and potentially dangerous component of the extremist right's belief systems, especially within the context of Identity.

This is the kind of element that a scene like the Schiavo case -- with all its attendant supercharged hyperbole -- was bound to attract. People like Gritz are drawn to these events like flies to cloaca.

And of course, when it all spirals out of control, people like Jeb Bush and Rush Limbaugh and Bill O'Reilly -- you know, those "mainstream" conservatives who have thrown gasoline on this bonfire at every step of the way -- will somehow find a way to blame the carnage on liberals.

No comments:

Post a Comment