I have at least a little sympathy for the main argument offered by the marine-park industry in favor of keeping wild killer whales captive: that they provide whole generations of children, and the public in general, with an up-close, concrete appreciation for these animals.

After all, I can date my own daughter's love of all things orca back to a visit to SeaWorld in San Diego we made back in the spring of 2003. At all of 20 months old then, she wanted mostly to spend the day at the big glass windows to the orca tanks, and of course I had to buy the stuffed orca doll. Even today her toy and book collections are riddled with killer whales.

And give the seaquariums credit: it was their exposure of orcas to the public through such venues that transformed the public perception of them from that of dangerous killers to cuddly sea mammals.

We were reminded this week, however, that the friendlier stereotype can be nearly as destructive, and that you cuddle them at your mortal peril: like Peter Pan's mermaids, "They'll sweetly drown you if you get too close." A SeaWorld orca named Kasatka injured her trainer with an unexpected display of threatening behavior:

- Park trainers were examining the whale, a female orca named Kasatka, and trying to determine what made her grab her trainer, Ken Peters, Koontz said.

... Peters, 39, remained hospitalized with a broken foot after the whale grabbed him and twice held him underwater during a show. He had a fractured metatarsal in his left foot but was in good spirits, Koontz said.

Peters was hurt around 5 p.m. Wednesday during the final show of the day at Shamu Stadium, a 36-foot-deep tank.

The show's finale called for Kasatka to shoot out of the water so Peters could dive off her nose. The whale is about 17 feet long and weighs well over 5,000 pounds.

As several hundred spectators watched, the whale and trainer plunged underwater, where Kasatka grabbed Peters by the foot and held him for less than a minute before surfacing, Koontz said.

"The trainer was being pinned by the whale at the bottom of the pool," Karen Ingrande told KGTV-TV.

When they came up, Peters tried to calm the animal by rubbing and stroking its back but it grabbed him and plunged down again for about another minute.

What's noteworthy about this is that Kasatka was exerting a high level of reciprocal control over the situation. A killer whale could snuff out the life of its trainer at almost any given moment: its jaws are capable of crushing large mammals to death instantaneously. Their tails are also capable of delivering crushing blows. If Kasatka had meant to harm Peters, she could have done so easily.

In spite of the incident, Kasatka was back performing today, and whale experts agreed that it was difficult to tell what set her off:

- Some experts agree the 30-year-old orca simply may have been having a bad day.

Kasatka may have been put out by a spat with another whale, grumpy because of the weather or even just irritable from a stomachache, they speculated.

"Some mornings they just wake up not as willing to do the show as others," said Ken Balcomb, the director of the Center for Whale Research in Friday Harbor, Wash. "If the trainer doesn't recognize it's not a good day, this will happen."

The Humane Society of the United States, which opposes keeping orcas in captivity, issued a statement Thursday suggesting SeaWorld may one day have to kill a whale to save a person's life.

"Simply put, keeping these powerful and intelligent marine mammals in captivity and allowing people to swim with them is utterly inappropriate," said Naomi A. Rose, marine mammal scientist for the society.

Rose has more than a point, because the double-edged sword of public exposure to captive orcas is that we get to see all too clearly that keeping these large wild animals penned up in limited concrete tanks is not good for the animals. And even worse is forcing them to perform stunts for the sake of entertaining crowds of people.

Certainly, that was our experience. Having seen them in the wild, I was disturbed by the limited nature of the captive orcas' existences: circling, circling, circling constantly in a featureless concrete tank whose sides constantly echo. For a creature whose primary mode of perception -- its echolocation -- is predicated on sound, seaquarium life must represent a kind of sterile hell. Particularly for a creature accustomed to roaming open seas at will. As much as I was pleased with her interest, I was disquieted by what we saw the orcas forced to endure.

It's not that I'm opposed to viewing wildlife in captivity -- we are frequent Woodland Park Zoo visitors as well. It's also knowing, from watching the Keiko saga up close, just how exceptional these animals are. Many animals are in zoos because they were injured and rehabilitated; for most of them, return to the wild is out of the question. For killer whales, it's the question.

Keiko -- who was a particularly bad choice for any effort to return to the wild, since he was captured at such a young age he had no hunting skills, and his family group was completely unknown -- overcame tremendous odds in any event and proved himself capable of living in the wild for the better part of a year, until he succumbed to disease. If Keiko could do it without familial support (which is usually critical to orcas' survivability), then there are a number of other candidates whose family groups we have identified -- notably Miami Seaquarium's Lolita and SeaWorld's Corky -- whose chances of success seem vastly better.

The case of Lolita is especially egregious; her decrepit tank in Miami is smaller than the tank in Mexico from which Keiko was so famously rescued. Since she was captured at age 7 and probably still has at least some hunting skills; since she still uses her L pod family calls; since we know almost precisely which family group (the L25 subpod) she belongs to; and since, at age 44, she is still in the middle of life (females in the wild can live to 90 years old) and in fine health; for all these reasons, she is one of the prime candidates for the return of a killer whale to the wild.

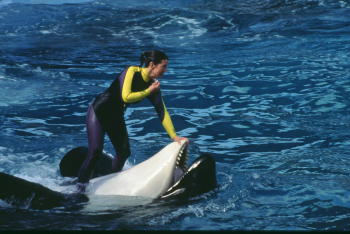

Note in the photo of Lolita above how her trainer is riding her; this practice has in subsequent years been stopped. But it was while performing a similar kind of stunt at SeaWorld that Kasatka injured her trainer.

This underscores, as many whale experts already know, that orcas really do not like to be ridden. Yet SeaWorld evidently persists in these kinds of performances. And that raises even more serious questions about making orcas perform for crowds generally. Marine-park owners and trainers insist that the orcas like it; but there are many indications that the rote nature of the performances may just be stifling and aggravating to the orcas, who are intellectually playful by nature. Certainly the sterile, cramped life inside the tanks is stifling for them. And eventually, some of them act out.

Though there has never been a recorded attack by a wild killer whale on a human, that is decidedly not the case in captivity. Erich Hoyt has documented the negative effects of captivity on killer whales and dolphins, and he vividly recalls the one case, here in the Puget Sound, where a captive orca actually killed its trainer, in circumstances horrifyingly similar to this week's incident:

- On February 20, 1991, University of Victoria marine biology student and part-time trainer Keltie Byrne, 20, slipped and fell into the orca pool at Sealand of the Pacific. She had just finished a show with the three orcas. Since Sealand trainers stay out of the water, she was not wearing a wetsuit. One whale took her in its mouth and began dragging her around the pool, mostly underwater. A champion swimmer who had competed at the international level, she was no match for three huge orcas determined to keep her in the pool. At one point she reached the side and tried to climb out but, as horrified visitors watched from the sidelines, the whales pulled her screaming back into the pool.

"I just heard her scream my name," said trainer Karen McGee, 25, and then I saw she was in the pool with the whales. "I threw the life-ring out to her. She was trying to grab the ring, but the whale, basically, wouldn't let her. To them it was a play session, and she was in the water." McGee and other Sealand staff tried to distract the whales by throwing them fish, banging on the water with steel buckets and giving them hand and voice commands. Nothing worked. Byrne came up screaming one more time and then, as the whale swam round and round the pool with Byrne in its mouth, she finally drowned. It was several hours before her body could be recovered.

She had ten tooth marks on her body, the largest on her left thigh, but was otherwise untouched. The whales had stripped her clothes off. "It was just a tragic accident," Sealand manager Alejandro Bolz told newspaper reporters. "I just cannot explain it."

There have been dozens of similar incidents, all dismissed as "isolated incidents." One of the earliest was at SeaWorld:

- In March 1987, at Sea World in San Diego, Jonathan Smith, 21, was in the water performing with the orcas before several thousand cheering spectators crowded into Shamu Stadium. A six-ton orca suddenly grabbed him in its teeth, dove to the bottom of the tank, then carried him bleeding to the surface and spat him out. Smith gallantly waved to the crowd - which he attributed to his training as a Sea World performer - when a second orca slammed into him. He continued to pretend he was unhurt as the whales repeatedly dragged him 32 feet (9.8 m) to the bottom of the pool, as if trying to drown him. He was cut all around the torso, had a ruptured kidney and a six-inch (15-cm) laceration on his liver, yet he managed to escape and get out of the pool.

... In recent years, with the proliferation of cheap video cameras, a number of incidents have been recorded. They range from bitings and collisions to near drownings when whales have held trainers underwater. Many of these dangerous incidents happened when the trainers were riding whales around the pool. Some former trainers such as Graeme Ellis believe that orcas, in general, do not like to be ridden. "They may tolerate it when they're young or new to captivity," says Ellis, "but later, it can lead to problems." Yet most marine parks still feature trainers riding orcas during the shows.

We made one more visit to SeaWorld in 2004, which included a "dinner with Corky" that was more disturbing for my daughter than fun. After that I was determined to make sure that when my daughter saw orcas in the future, it would be in the wild, where they belonged. And I've followed through on that.

I'm not entirely opposed to limited captivity for killer whales, because I do recognize that they serve a genuinely educational purpose. Certainly, for orcas born in captivity, a return to the wild is not an option. Paul Spong has proposed replacing the current captivity system with an "ambassadors" program under which a limited number of whales are captured annually for a short number of years and then returned to their families; while not ideal, it would be superior to the current system, under which orcas from communities that are not as thoroughly studied as those in the Pacific Northwest -- notably those in Iceland -- are still commonly and wantonly captured for marine parks.

The marine-park industry owes it to the animals themselves to make a good-faith effort to facilitate a return to the wild for those animals that are potential candidates; and they owe it to the species to subsidize the research necessary to assess the impact of their captures on those communities (such as those in Iceland and the Antarctic) where killer whales are still being taken.

Unfortunately, the industry has been steadily opposed to any measures even potentially leading in this direction, which tends to underscore that the high-minded environmentalism they sell alongside their cuddly dolls is really just for show, like the orcas: the bottom line is still the bottom line.

Which is why incidents like this week's will crop up from time to time. These "isolated incidents" will continue until the public takes note of the real problems -- both behavioral and ethical -- posed by forcing killer whales to perform stunts for public entertainment.

Let's face it: killer whales would still enthrall and entice and educate children simply by being themselves in captivity. The performances serve no real purpose except to make money for the marine parks. Cutting them out might dilute the parks' bottom line, but it would make their captivity at least a little less stultifying and difficult.

Marine parks are a fine idea -- if executed with the animals' well-being first in mind. But the public needs to demand they do so.