[Note: Contains spoilers.]

One word kept tumbling through my mind as I watched Apocalypto, Mel Gibson's profoundly racist depiction of Mayan civilization on the verge of collapse:

Bogus.

Or variations thereupon. As the movie proceeded, my notes read something like this:

- Uber-bogus.

Bogalicious.

Bogosity.

I'm being bombarded with bogons!

Aiiee!!! Quantum bogosity!

Sure, the movie is imbued with a Sepulvedan racism. It's also stomach-churningly violent even as it lectures us about the perils of moral decay (note to Mel: I hear from morally upright folks all the time that a taste for excessively violent entertainment is a strong indicator of moral decay). And there are plenty of the details of Mayan culture that he gets wrong, too (more on that later).

But Apocalypto is bogus on so many levels, including the simple elements of its plotline, that it's difficult to recommend it even as a piece of fantastic cinema. It's not even a particularly good chase film, which is what Gibson says he set out to make here.

For one thing, there really isn't much of a plot: Young Mayan jungle hunter Jaguar Paw is kidnapped for human sacrifice by the evil Mayan city dwellers, though he first manages to secrete his pregnant wife and young son at the bottom of a dry cenote. Once in the city, said sacrifice is interrupted by the surprise appearance of a total eclipse. Jaguar Paw is then forced to flee a pack of vengeful Mayan warriors when he kills the leader's son while escaping. Long pursuit then follows through the jungle, where Jaguar Paw manages to outwit his pursuers, picking them off one by one until only three, including the Vengeful Father, are left. He kills VF with a tapir trap introduced in the opening scenes. Then, with the last two warriors in pursuit, he runs out onto the beach and discovers a small flotilla of Spanish ships, with soldiers and priests in the process of rowing ashore. The remaining two pursuers, agape, go out to meet the strangers, while Jaguar Paw sneaks back to rescue his wife and child, whose hiding place has since been filled with rainwater. We last see the young family heading off into the deeper parts of the jungle together.

The chase scenes are not particularly imaginative, though Gibson manages to mix in the expected obstacles: waterfalls, mudpits, jaguars. And the yawning predictability of the whole affair doesn't exactly enhance the suspense. I mean, didn't we see this basic plotline 40 years ago in The Naked Prey?

Still, on a pure popcorn-munching level, Apocalypto has at least a decent level of suspense to hold your attention throughout. That, and the crisp-yet-lush cinematography, are about all it has going for it. But if you're looking at all for an authentic representation of pre-colonial life in the Yucatan, this movie ain't it. It's just bogus, from start to finish. Especially the finish.

Now, no doubt my experience was negatively affected by knowing a little more about Mayan culture than the average American moviegoer who is Gibson's audience. But you don't have to know much about the Mayans to realize that what ensues in Apocalypto just doesn't make any sense, even within the context of its own self-created world.

The most obvious example comes in the movie's central set piece: the sacrifice scene atop the temple in the Mayans' stone city. Just as Jaguar Paw is about to have his heart cut out on the altar atop the temple stairs, a total eclipse of the sun occurs, driving the populace below into a confused frenzy. The priests declare the gods satisfied, and let Jaguar Paw and his fellow captives off the hook, so to speak.

Huh? OK, nevermind the fact that Mayans not only regularly predicted astronomical events, they actually designed their temples and cities and religious ceremonies around such events as solstices and eclipses. Nevermind that they would have been eagerly anticipating any such eclipse.

Let's just pretend, for the sake of argument, that nobody knows this (even though they teach it to sixth-graders nowadays) and that the story exists in its own vacuum. It still doesn't make any sense.

It's obvious, after all, that these priests need a pretty steady supply of warm bodies to keep trooping up the stairs and have their hearts cut out and heads cut off. After all, we not only see a steady flow of headless corpses to join a large pile at the bottom of the pyramid, we later see Jaguar Paw staggering through an entire Holocaust-sized dumping ground full of similar corpses.

So why, exactly, do they let these intended victims go? Even if the day's ceremonies were at an end, they obviously could be imprisoned for use on the next day. And if you're going to let them go, why only turn them back over to their murderous captors for death at their hands (which is what befalls everyone but our protagonist)?

Why? Because Mel wanted to make a chase movie, dammit. Logic be damned.

There are plenty of other such instances in which the basic premises of the movie simply don't add up. One of the key plot points -- the jungle dwellers' vulnerability to capture, a product of their utter ignorance of the existence of urban Mayans -- might have been plausible in the proto and early Classic Mayan period (150 B.C.-500 A.D.), but at the period in which it is supposed to take place, that is, at early Spanish contact in the 16th century, city-building Mayas had been a common and significant feature of the Yucatan, Guatemala, and Belize for over a thousand years. It simply is not credible that people living anywhere in their vicinity would be unaware of them.

This is where just a little knowledge of Mayan society makes Gibson's lapses look almost comical, were the upshot -- depicting Mayan life as relentlessly savage and brutish, even in its most "idyllic" state -- not so repulsive. Indeed, the chief narrative of the innocents' village life that Gibson depicts involves the public humiliation of a young married man over his sex life. The whole scene plays like Spanish colonists' depictions of native Mesoamericans as sexually wanton and primitively ribald.

Yet the reality was that there is no evidence that there ever were such jungle dwellers in Mayan society, at least of the kind depicted here. There were many thousands of Mayans who dwelt in the jungles, but they were primarily farmers who supplemented their diets with hunting and fishing. These farms were called milpas, and before there were even cities these formed the backbone of Mayan society.

These farmers usually lived in villages about the size of that shown in Apocalypto, but these villages were uniformly surrounded by the milpa fields, growing maize, beans, and squash, which usually constituted several acres of cleared-out jungle. Like most agrarian societies, they were highly ritualistic, building and arranging their lives according to long-established customs and ceremonies, including the very architecture of their homes.

We don't know a lot about their sex lives, except that the Mayans prohibited adultery and were not particularly promiscuous. More likely Mayan villagers would have been frowning at the kind of scene Gibson depicts than laughing.

Perhaps more to the point, the urban Maya had a powerful symbiotic relationship with the agrarian villagers, since the milpas also were their primary source of food. Trade with the farmers was a long-established facet of Mayan life. As David Freidel and Linda Schele put it in A Forest of Kings: The Untold Story of the Ancient Maya:

- In times of general prosperity, which existed for most of the Classical Maya periof, the common folk enjoyed ready access to the basic necessities of life, both practical and spiritual. In times of hardship and privation, the commoners and nobles all suffered alike. The ancient Maya view of the world mandated serious and contractual obligations binding the king and his nobility to the common people. Incompetence or exploitation of villagers by the king invited catastrophic shifts in allegiance to neighboring kings, or simple migration into friendlier territory. Such severe exploitation was a ruler's last desperate resort, not a routine policy.

So not only is it beyond unlikely that a Mayan forest villager would be unaware of urban dwellers, but it's likely only in the remotest circumstances that these urban dwellers would be taking captives from the jungle.

Mayans did engage in plenty of wars, and they did decapitate plenty of sacrificial victims. But these victims were almost uniformly soldiers captured on the field of battle from opposing armies. Mayan warfare, like that of the Aztecs, was predicated on taking captives rather than slaying armies on the field of battle; for the Mayans, these captives were then used as slaves, as participants in their ritualized ballcourt games (which also featured decapitations), or as victims of bloodletting rituals.

The temples on which these sacrifices occurred, in Gibson's centerpiece sequence at the city, are clearly based on the temples at Tikal in Guatemala, which were a product of the Classic Maya culture. The best-known is Temple I, which was built around 695; but Tikal was abandoned by the end of the 10th century. It is particularly recognizable because of its steep angles and high crown, which were not features of most later Mayan temples, particularly not in the Yucatan. These later temples, such as the famed Castillo at Chichen Itza, or the extraordinary Pyramid of the Magician at Uxmal, were less steeply angled and broader-based.

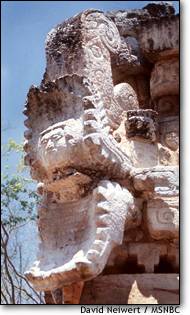

The temples on which these sacrifices occurred, in Gibson's centerpiece sequence at the city, are clearly based on the temples at Tikal in Guatemala, which were a product of the Classic Maya culture. The best-known is Temple I, which was built around 695; but Tikal was abandoned by the end of the 10th century. It is particularly recognizable because of its steep angles and high crown, which were not features of most later Mayan temples, particularly not in the Yucatan. These later temples, such as the famed Castillo at Chichen Itza, or the extraordinary Pyramid of the Magician at Uxmal, were less steeply angled and broader-based.So Gibson gives us a Tikal-style pyramid, even though none of the extant Mayan temples in use at the time of European contact would have looked like it. And then, in the scene atop the temple, we see up close that it is adorned with a fantastic panoply of Chaac rain-god masks and snake faces.

These too were common in certain Mayan cities, particularly the Puuc style of architecture found in post-Classic cities like Uxmal and Sayil. These are all in the eastern Yucatan, far removed from Tikal, and were created mostly after A.D. 900, by which time Tikal had been largely abandoned.

These too were common in certain Mayan cities, particularly the Puuc style of architecture found in post-Classic cities like Uxmal and Sayil. These are all in the eastern Yucatan, far removed from Tikal, and were created mostly after A.D. 900, by which time Tikal had been largely abandoned.So what Gibson gives his audience is actually a bizarre mishmash of Mayan styles, grabbed from different eras and different regions and slapped together, suggesting if not a disrespect at least at a willful ignorance of Mayan culture. This would not be so bad in a transparently inauthentic film, but Gibson parades his "authenticity" throughout the affair, insisting the script be in Yucatec Mayan (even though none of the speaking cast is a native Mayan speaker) and making brief nudges at authenticity by at least pilfering authentic Mayan styles for his mishmash.

What's noteworthy also is what Gibson fails to show. There is no indication that the Mayans possessed a refined sense of art; that they had written a large body of literature; that they had a deep sense of religious faith as well as deeply refined notions of honor that made them extraordinarily vulnerable to white invaders. We get no sense of their scientific achievements, which ranged from astonishing astronomical precision to acoustic wonders built into their architecture. We don't even get a glimpse of the Mayan ballcourts, one of their more interesting creations, or the games played on them (which actually might have offered Gibson even more opportunities for gore).

But then, showing these aspects of Mayan culture would have countered the point that Gibson appears intent on making: that Mayan civilization was irredeemably corrupt, and that was why it fell. Even if the historic record tells us otherwise, Gibson's thesis, drawn straight from the worldview of the 16th-century Catholics who constantly touted the natives' barbarism as a reason for destroying them, comes before any deeper contemplation into the real causes of the decay of this civilization -- which, besides the costs of its frequent warring, almost certainly included environmental disasters and disease.

That brings us, finally, to Gibson's Big Point. He clearly intends to draw a parallel between the Mayan civilization and our own. If we read the analogy correctly, Gibson is essentially depicting American civilization as morally decadent and corrupt, innately violent and antagonistic to freedom. Apocalypto is intended as a warning about our imminent demise as a civilization corrupted from within.

No doubt there is some resonance to this thesis, especially in a time when we're sending off American soldiers to die in Iraq, a kind of public sacrifice on the bloody altar of our government's imperialist designs. But neither modern American culture, nor ancient Mayan culture, has ever been as relentlessly evil as the civilization he depicts in this film.

We can understand, given Gibson's well-established propensity for a medieval Catholic worldview, which goes hand-in-hand with his remarkable propensity for sadistic onscreen violence, why he might hate the Mayan civilization enough to depict it the way it does. But why, exactly, does Mel Gibson hate America?

And why, exactly, does he stoke our appetites for grotesque violence even as his film preaches to us about the dangers of such inhumanity?

Answer: Because Gibson, like his movie, is bogus. From start to finish.

UPDATE: Marcello Canuto, an actual Mayan scholar (and not a mere amateur like myself) weighs in on some of the same points, and much more, in Salon. (I only saw this piece after posting this review.)

No comments:

Post a Comment