-- by Sara

Dave and I refer often to James Loewen's research on "sundown towns" -- American towns that once had small African-American communities -- which, at some point, simply up and vanished.

The historical fact is that if you're a middle-class white American living in the north or west of the country, the odds are overwhelmingly good that the town you live in, right now, is a sundown town -- or was one at some point in the not-so-distant past.

This fact came home forcefully to Loewen as he studied the censuses of small towns and suburbs all over America. After the Civil War, newly-freed black families spread out across the country, looking for places to start over. By 1890, there was hardly a town in America that didn't have at least a small community of black tradesmen or farmers -- aspiring families putting down roots and planning better futures. There was no town too small, no corner so remote, that a handful of African-Americans didn't take refuge there -- hoping against hope they'd finally found a place that was far enough away from Jim Crow.

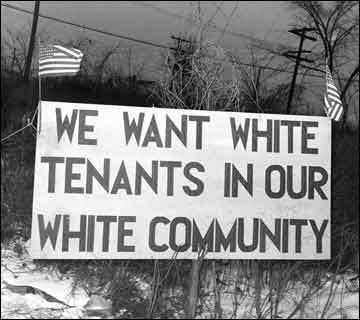

But Loewen noticed something else. Starting in the 1890 census -- and continuing up until the 1950 one -- these communities started to vanish from the census figures. Towns that had 50 or 60 African-Americans in one census had exactly zero in the next. It was like watching these small lights just wink out, as these communities one by one went sundown.

As I said: if you live in a predominantly white town or suburb, the odds are overwhelming that one of them was yours. It wasn't an accident. It didn't happen just because the houses were too expensive, or the winters were too cold, or they just never got around to moving there. Loewen's research shows that black families settled absolutely everywhere -- almost certainly including where you are. The reason they're not there now is that somebody in your community, at some point in the past, decided to force them out.

This happened in a couple of different ways. Loewen notes that when he began his research, he assumed he'd find three different types of all-white towns. First, there were the small towns that had deliberately sundowned themselves at some point. Second, there were sundown suburbs, which were built from the beginning with restrictive covenants excluding blacks, Asians, and often Jews. Third, he expected to find places that where African-Americans had simply never bothered to go -- places that were all-white by accident. As his project progressed, however, Loewen found that every all-white town he found fit into one of the first two groups; and that, statistically, the third group simply didn't exist at all. He was shocked to discover that sundowning and covenanted suburbs, between them, told the entire story of all-white America.

This is one enormous and still very-much-present piece of our silent shared history that black Americans know and white Americans do not. African-Americans have a completely different sense of geography than white Americans do: even now, there are places they avoid, places they know they're not welcome, places where they expect to find trouble. I have African-American friends my own age who remember being on road trips with their parents in the 1970s, overhearing the quiet debates between the adults in the front seat over whether or not this town was a safe place to stop. I've also been on the other end of this myself, when I was 15 and working my first job in a diner attached to a motel. Once in a while, the manager would get a phone call from a motel at the other end of town, warning him that a black family had come in to try to get a room. The motel managers' phone tree went into action, and within 5 minutes every "No Vacancy" sign on Main Street would suddenly flicker on -- including ours. Going north or south, it was a three-hour drive to the next town where a black family could get a room. And they'd have no choice but to drive it --civil rights laws be damned.

Also: remember that it wasn't just African-Americans that were sundowned out. The Chinese were expelled from many towns across the West (including almost the entire states of Idaho and Wyoming) in the early part of the last century. Japanese communities relocated after the exclusionary acts of the 1920s, and many disappeared completely after the World War II internment. The white-hot animus we see against Latino immigrants in so many towns and suburbs today has a long and sordid history. These people have good reason to believe they can turn back the tide: they know that their own grandparents were very successful in expelling non-whites in the past, and in many cases there's a perverse sense of obligation to maintain that legacy for the generations to come. Uncovering and confronting that past gives us a powerful way to confront the would-be sundowners who are still in our midst today.

A word of warning

Loewen issues a serious warning that digging up this secret history is painful. Even today, there are probably people in your town who are very invested in not going there. They don't want to face up to the ways their parents behaved and thought, or the things their grandparents did. They don't want to give up the polite fiction that they're not racist, or are contributing to the perpetuation of a racist society. They don't want to give up a history that, in the backs of their minds, justifies continued exclusion. And, perhaps worst of all: They're afraid they'll find they owe someone something.

And they do. At the very least, they owe their children the truth. At most, they owe America the chance to heal its deepest racial wounds. Outing sundown towns, one by one, may be our last best chance for this long-awaited healing to finally begin. The good news is that it's something we can do locally. Uncovering a town's racial history can be a soul-changing service project for a church or civic group, or an engrossing task for a high school history class. Or you can do it on your own or with a few friends, sleuthing around in your spare time to discover pieces of your local past that can have an important impact on its future.

But don't kid yourself: one of the things you will certainly be forced to confront is the deep-seated racism of people you might never expect it of.

So, how do you out a sundown town? For those willing to take up the challenge, Loewen lays out the following plan of action.

Step 1: Start with the census

The census figures for your town will tell the whole story at one glance. Your local library will have the local census going back to the city's founding; or you may be able to pull the data up online at www.census.gov. (Loewen warns that this is not an easy site to use; and my own experiments with it lead me to echo that warning.) Click on Census 2000 (even if you're looking for 1910); then look for the list of censuses for previous years. You may or may not find the year you're looking for. It may take some wandering around the site to find the data for the year, state, and town you're looking for -- a search that's made more complicated by the fact that the data for different decades are recorded according to different systems.

You're looking for the town's decade-by-decade population breakdown by race; and also by age and sex. Early census figures aren't as reliable or detailed as later ones; and it's not unusual to discover that there's no race data at all, especially for towns with a population under 2500. But from 1950 on, the figures should be reliable and quite detailed.

Look at the overall county census data, too. You may have a better chance of finding a racial breakdown. And note, too, that it was common for entire counties to go sundown at once. Loewen also point researchers to the University of Virginia's Fisher library census database, which offers census data by county and is much easier than census.gov to navigate.

Loewen's own Sundown Towns website also has census figures for the towns he's investigated, along with the data and anecdotes he's collected from thousands of sundown hunters working across the country. This is a not-to-be-missed first stop on your search. If your town is there, it will give you plenty to start with. If it's not, looking at the known sundown towns in your region may give you some insight into the timing and causes of possible sundowning.

Once you've got the figures, what are you looking for? Loewen noted several patterns that point to a possible sundown town:

-- Look for a sudden drop-off in a minority population. If the town had 200 blacks in 1920, and 12 in 1930, it's a clear sign that something happened in the course of that decade to change the demographics. It's a strong suggestion that a) sundowning happened; and b) this is decade you should focus your further research on.

-- Be suspicious if there are fewer than ten members of a given minority in a small town. In a larger city, look for an African-American (or Asian) population under 0.1%. There were often a few token people who were allowed to stay on in town provisionally: usually, they offered an unusual trade or service that a small town relied on, and were thus granted an exception to the sundown rules.

-- Look for great disparities in gender. Loewen notes that in covenanted suburbs, a female-to-male ratio above two-to-one indicates that the minority population comprises mostly live-in domestic servants. Even if the number of blacks is quite high, the town is effectively sundowned, since black families aren't allowed to live there.

-- Look at the age range of the minorities you find. If they numbers are concentrated in the 19-34 age range, it suggests there's an institution of some sort that's housing them -- another sign that minority families were discouraged from settling there.

Step 2: Visit the library

Actually: visit two. Go to the one in your town; and then also plan to make a trip to the county library's main branch at the county seat. Each library will have a local history department. (In some libraries, it's just one shelf; in others, it may be its own separate room.) Read through those local history books. If you've found the decade when the sundowning apparently happened, this will narrow your search -- but pay attention to the decades just before and after, too. What were the big issues and changes in that decade? Was there a major economic shift that brought in new groups, or brought hardship to existing ones? Who were the leaders in town at the time, and how did they manage these changes? The goal here is to gather hints as to what might have triggered the sundowning.

Don't expect to find any references to sundowning, or expulsion of certain minorities. There will be nothing about it being a sundown town, or exclusive in any way. But, even so, you may find little factoids that you can begin to draw inferences from.

You might also ask to look through the area's major newspaper for that decade. It can take a few hours to review ten years' worth of a weekly paper, but you may find hints of social and economic shifts that may have precipitated sundowning; or real estate ads that lay out the terms under which new covenanted subdivisions were first sold. (Racial exclusivity was often a major selling point, and either hinted at or overtly spelled out in the ads.)

In towns that predate the Civil War, Loewen suggests taking a close look at the town's Civil War history. Was it mainly Democratic or Republican around the time of the Civil War? Did it go for Douglas or Lincoln in 1860? Democratic towns, or those that went for Douglas, are more likely to have sundowned later on, since the 19th century Democrats were the party of white supremacy. Also: what do the histories say about the Civil War itself? In some northern towns, you'll read that the war was fought to hold the country together and eliminate slavery. If it mentions slavery as a cause of the civil war, that may be a hint suggesting positive local attitudes toward African-Americans. Also: how did the local boys go to that war? Were they drafted? Did they volunteer? Were there draft riots? A town that resisted going to war may have had more negative attitudes toward blacks.

Step 3: Take it to City Hall

Armed with proof of a racial shift, and some historical hints about how it might have happened, your next stop is City Hall.

First, sift through the city council minutes of your target decade (and, perhaps, the one or two decades before), looking for ordinances or other discussion regarding racial events. Loewen has yet to hear of a written sundown ordinance anywhere -- but there may have been other policies enacted that were effectively racist even if they weren't overtly so.

Next, look at the property deeds for various neighborhoods. Some may have names indicative of a black population ("Black Hills" or "Black Creek," for example). Look particularly for black churches, such as African Methodist Episcopal churches, and look at the dates on their deeds. If they sold their church building and didn't build a new one, that may be because they were being sundowned out. Read the original deeds for the elite suburbs, too: many of these were built as white neighborhoods, covenanted from the beginning to ensure no minorities would never live there.

Step 4: Talk to people

Since the sundowning movement started in 1890 and ran up until 1950 -- and covenanted suburbs were being built right up until the Fair Housing Act of 1968 -- odds are good you can find some old-timers who remember this first-hand, or at least have it second-hand from parents or grandparents who were there. Loewen suggests that the main purpose of the earlier research is to provide a foundation that will enable you to find these people, and ask the kinds of questions that will yield a rich oral history of what happened.

Start with the librarians at the two libraries. There's usually one in every town library who specializes in local history, and who can be a tremendous resource -- or something of a barrier, depending on how strongly he or she is invested in promoting a feel-good narrative of the area's past. Loewen finds that it's useful to start the conversation on some topic other than race relations. Ask about population variations over time: "I notice Smithville did very well through the Depression..." Ask about those economic and demographic shifts in the decade that you're focusing on. Only after that person's comfortable do you ask about the declines in black population that showed up in the census figures.

The local historical and geneology societies are your next stop. "The geneologists are often very useful: they love stories about the black sheep in families, and will dish enthusiastically," says Loewen. On the other hand, he warns that historical societies are often (either officially, or in their own minds) a de facto branch of the Chamber of Commerce. They may try to give you the best possible gloss, and will offer nothing incriminating in writing. On the other hand, a sympathetic member may tell you things off the official record that can take your search all kinds of interesting places.

There are two important questions to ask everyone you talk to. The first one is: "How do you know what you're telling me?" Did they see sundown signs themselves? (Of course, many towns never bothered to put up signs.) Were there ordinances? Did they hear family stories? Was there police harassment? (Though actual ordinances are very rare, police typically enforced this unwritten law anyway.) Oral history is tricky business, because so much is unverifiable. Asking "How do you know this?" about every story you hear will help you assess the veracity of the tales.

The second question is: "Who else knows the history around here?" Keep following up, and eventually you'll find the people who can validate what you've already heard; and help you piece together what happened, when, for what reasons, and under whose instigation.

Step 5: Go public

Loewen stresses that it's important not to go public with your project until after the bulk of your research is done. He suggests that the best strategy is to get the early research done quickly, before word gets around. People may be far less likely to want to talk to you once they know what you're up to.

Once you've got the goods, write an article. Start talking to church, school, or service groups. Make a presentation to the historical and geneological societies. Loewen believes that that this information empowers people: in many towns, having this piece of history exposed is the first step in a larger truth and reconciliation effort that can put the future on an entirely different path.

According to Loewen, towns that remain overwhelmingly white need to take three steps to get over it:

1. Admit it. Being confronted with the particulars of their own local history helps.Most importantly, it may mean talking, openly and honestly, about what kind of community you want to be. Sundowning and covenanting directly created the urban ghettos of the 20th century: black America settled in the inner cities because it literally had nowhere else to go. Reversing that trend, and restoring the right of all Americans to live and travel where they please, is the first step in reversing a whole cascade of other social ills that still proceed from a century and a half of segregation.

2. Apologize. Make amends. Put up an exhibit in the local history museum; find ways to discuss and commemorate these events and ensure they won't evaporate again from the local historical narrative.

3. State that you don't do it any more -- and mean it. This may mean educating real-estate agents who still quietly practice "steering." Or having a parents' group visit the schools, talk to the teachers, and review the history books to find out what the kids are learning about both national and local racial history. What's being slid under the rug? Is the teacher qualified? (Loewen notes that nationally, there are more history teachers teaching out of their field than in any other subject, especially in the south and midwest. Furthermore: a striking number of these are sports coaches.) Or educating business people on the ways ethnic and racial diversity increase the economic prospects of an area, pointing out that the most depressed parts of the country are invariably also the most segregated ones.

The sins of the past are only sins now if you're still engaging in them. This is one sin we have a chance to put a real, history-making stop to -- in ones and twos and small groups, working from our living rooms and church basements, in the perceived safety of our all-white enclaves where race only apparently ceased to be a question a very long time ago.

No comments:

Post a Comment